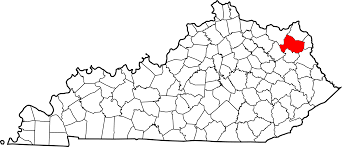

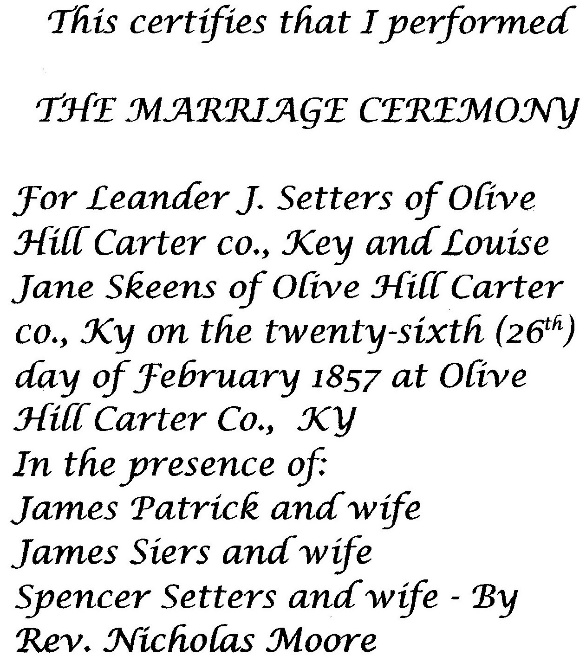

Leander Justis Setters and Louisa Jane Skeens, both of Carter County, in the Northeastern part of Kentucky, not far from the Ohio River, were married, the 26th day of February 1857. Fewer than three thousand people lived in the entire county when both were born at Olive Hill. In fact, the county was formed just ten months before Louisa was born. They were married in a ceremony performed by a Reverend Nicholas Moore.

Leander was about seventeen years old, Louisa about nineteen. Louisa was born in 1837, just thirty-two years after the death of Martha Washington, our “first” First Lady of the United States. When Louisa entered the world the famous Wild West Character, Wild Bill Hickock, was just six months old. Her father-in-law, George Washington Jordan was born just fifteen years after his namesake, the real George Washington, who died eleven days before Christmas, in 1799. This meant that Leander’s grandfather was probably a teen-ager when George Washington was standing in that little boat (if, indeed he did) while crossing the nearly frozen Delaware River. Was there a reason Leander’s father was named George Washington Jordan? I mean, other than just patriotic admiration?

One of the witnesses to the wedding was Spencer Setters and his wife. No mention is made as to the relationship to Leander. Nor is Spencer ever mentioned again. Spencer, as it turns out, was an uncle of Leander, the brother of Perlitha, Leander’s mother. To further complicate things, by this time, Perlitha, had remarried after leaving George Washington Jordan and Returning to live with her father, Uriah, a veteran of the War of 1812. Perlitha began having babies again with her new husband, a Mr. Zornes.

Just one week after Leander and Louisa said I do, the United States Supreme Court held that Black People, enslaved or free, could never become citizens of the United States and that African Americans, in essence, had no rights at all and were mentally inferior to whites. The ruling came after a ten-year legal battle by a black man to gain his total freedom.

It was a strange culture into which these two white Kentucky folks were marrying. It was not until 1862, five years later, that slavery was abolished during the terrible United States Civil War. The courts ruled that the slave owners should be reimbursed for their loss of property, the slaves, but the slaves, themselves, were not to be paid anything. Most slaves had no property, could not read and, other than working in the fields, had virtually no skills. They were just trotted out to the road and told to do the best they could. Life for these two white teen-age newly-weds was complicated, to say the least.

The absolute reduction of women being reduced to mere property, at least in name, was one of the prime motivators of the author to name this story, “LADIES OF THE LAKE.”, knowing full well, the title of the book, or

The absolute reduction of women being reduced to mere property, at least in name, was one of the prime motivators of the author to name this story, “LADIES OF THE LAKE.”, knowing full well, the title of the book, or

Website story would not be attractive to those with a hint of masculinity guiding their choice of reading material.

He did so out of respect for his own mother, and his own wife, and the millions of women whose lives were simply reduced to being the property of those to whom they legally, but not for that reason, were bound. But it was a terribly complicated culture for all young people, black and white, especially the blacks. About eighty years after that wedding, Leander and Louisa’s granddaughter, Bertha, brought James Robert Setters, the author of all of this, and Leander and Louisa’s great-grandson, to a museum, in Kentucky that featured the cabin where Abraham Lincoln, whose presidency brought about the end of slavery in the United States, was born.

Read the preacher’s report on the Wedding of Leander and Louisa.

See how wives have been reduced to just that? No names, for females, just the names of witness and “wife.” It would have been a monstrous surprise for all of them to know that in just one hundred years after Leander and Louisa were married that a black man would be elected the President of the United States, and eight years later a woman would be running for the office of President. She did not make it, but she came very close. In fact, more people voted for her than her male opponent. But the electoral vote favored him. But a woman, “a black woman”, was elected as Vice-President 173 years after Leander and Louisa, said “I DO”. Louisa meant that, more than Leander. It was the culture of the times

See how wives have been reduced to just that? No names, for females, just the names of witness and “wife.” It would have been a monstrous surprise for all of them to know that in just one hundred years after Leander and Louisa were married that a black man would be elected the President of the United States, and eight years later a woman would be running for the office of President. She did not make it, but she came very close. In fact, more people voted for her than her male opponent. But the electoral vote favored him. But a woman, “a black woman”, was elected as Vice-President 173 years after Leander and Louisa, said “I DO”. Louisa meant that, more than Leander. It was the culture of the times

SPEAKING OF WHAT MODERN WOMEN CAN DO

Your author now calls on Peggy Noonan who wrote in detail concerning the outcome of the personalities involved in the surrendering progress of the Civil War.

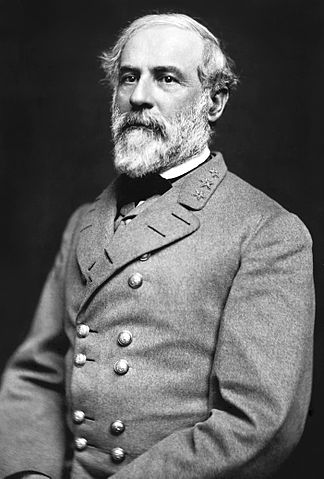

These two Generals are the ones who actually felt the war had run its course and the time had come to let bygones be bygones: Ulysses Grant and Robert E. Lee.

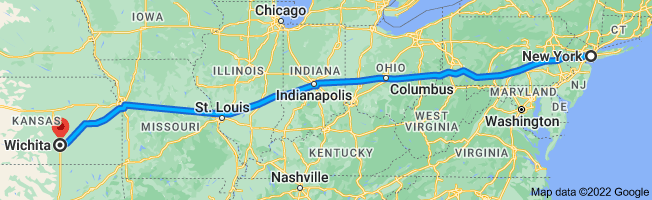

But first let’s talk about her, Peggy Noonan who was born in New York City, N. Y. in 1950, the year that Dana Chapman and Jim Setters were married, in Wichita, Kansas, six states away

Working as a waitress, Noonan attended Fairleigh Dickinson University at night, earning a BA in English. Raised a Democrat, Noonan grew disenchanted with the antiwar movement and the student counterculture, gradually becoming a conservative. In 1974 she began writing news at radio station WEEI, then the CBS affiliate in Boston.

Noonan later became a producer at CBS TV, in New York, where she wrote and produced Dan Rather’s daily radio commentary.

In 1984 Noonan became a speechwriter and special assistant to President Ronald Reagan. Later she was named chief speechwriter for Vice President George Bush during the 1988 presidential campaign. After Bush’s defeat, she returned to New York to write.

Peggy is the author of several books, What I Saw at the Revolution: A Political Life in the Reagan Era, (1990); Life Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness, (1994); On Speaking Well, (1998); The Case Against Hillary Clinton, (2000); and John Paul the Great: Remembering a Spiritual Father (2005).

In addition, Noonan is a contributing editor for The Wall Street Journal, Time magazine, and Good Housekeeping.

America’s Most Tumultuous Holy Week

America’s Most Tumultuous Holy Week

By Peggy Noonan

columnist, political writer

ROBERT E. LEE SURRENDERED TO ULYSSES S. GRANT, AND LINCOLN WAS DEAD BY EASTER.” The Wall Street Journal

‘ Peace in Union’ painting by Thomas Nast

It was the Easter of epochal events. All that Holy Week history came like a barrage. It was April 1865, the Civil War. No one touched by that war ever got over it; it was the signal historical event of their lives, the greatest national trauma in U.S. history. It would claim 750,000 lives.

(Author’s notes: this compares to total deaths in China of FIFTEEN MILLION people during WW 2.

Everyone knew the South would fight to the end, but suddenly people wondered if it was the end. Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army was trapped and under siege in the middle of Virginia. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was bearing down, his army going from strength to strength.

The two exchanged letters under flag of truce. Grant to Lee: Did the general not see the “hopelessness” of his position? Lee sent a roundabout response, Grant, a roundabout reply, but he was starting to see; Lee knows he is beat.

On the morning of April 9, Palm Sunday, Lee sent word: He would discuss terms of surrender. They met that afternoon in the Appomattox home of Wilmer McLean.

Lee got there first. Allen C. Guelzo, in his masterly “Robert E. Lee: A Life,” quotes a reporter from the New York Herald who had joined a crowd outside.

Lee got there first. Allen C. Guelzo, in his masterly “Robert E. Lee: A Life,” quotes a reporter from the New York Herald who had joined a crowd outside.

Allen C. Guelzo

In truth, Lee didn’t know what to expect. He’d told his staff, “If I am to be General Grant’s prisoner to-day, I intend to make my best appearance.” His close friend Gen. James Longstreet thought Lee’s fine dress a form of “emotional armor,” an attempt to conceal “profound depression,” according to Ron Chernow’s superb, compendious “Grant.”

Grant, who at 42 was 16 years Lee’s junior, arrived a picture of dishevelment—slouched hat, common soldier’s blouse, mud-splashed boots. He was painfully aware of how he looked and feared Lee would think him deliberately discourteous; Mr. Chernow writes. Later, historians would think he was making a political statement, but he’d simply outrun his supply lines: his dress uniform was in a trunk on a wagon somewhere.

But he projected authority. Joshua Chamberlain, hero of Gettysburg, wrote that he saw Grant trot by, “sitting his saddle with the ease of a born master. He seemed greater than I had ever seen him, a look as of another world around him.”

The armies of the North and South, in blue and gray, were massed uneasily beyond the McLean House.

Neither Lee nor Grant wanted them to resume the fight.

Some of Lee’s officers had urged him not to surrender but to disband his army and let his men scatter to the hills and commence a guerrilla war. Lee had refused. The entire country would devolve into “lawless bands in every part,” he wrote, and “a state of society would ensue from which it would take the country years to recover.”

The generals sat in McLean’s parlor and attempted conversation. But of course, it is the surrender agreement, on whose terms they quickly agreed, that will be remembered forever.

The generals sat in McLean’s parlor and attempted conversation. But of course, it is the surrender agreement, on whose terms they quickly agreed, that will be remembered forever.

Lee’s army would surrender and receive parole; weapons and supplies would be turned over as captured property. Officers would be allowed to keep their personal sidearms.

Lee suggested Confederate soldiers be allowed to take home a horse or mule for “planting a spring crop,” Mr. Guelzo writes. Grant agreed, and Lee was overcome with relief. Lee then asked Grant for food for his troops. They had been living for 10 days on parched corn. Grant agreed again and asked how many rations were needed. “About 25,000,” Lee said. Grant’s commissary chief later asked, “Were such terms ever before given by a conqueror to a defeated foe?”

Lee suggested Confederate soldiers be allowed to take home a horse or mule for “planting a spring crop,” Mr. Guelzo writes. Grant agreed, and Lee was overcome with relief. Lee then asked Grant for food for his troops. They had been living for 10 days on parched corn. Grant agreed again and asked how many rations were needed. “About 25,000,” Lee said. Grant’s commissary chief later asked, “Were such terms ever before given by a conqueror to a defeated foe?”

Grant asked his aide Ely Parker, an American Indian of the Seneca tribe, to make a fair copy of the surrender agreement. According to historian Daryl Watson, Ely S. Parker was a Seneca Indian born in 1828 on the Tonawanda Indian Reservation in western New York. The Senecas were one of the tribes of the great Iroquois Confederation called the Six Nations. By the time of Parker’s birth, this once powerful confederation had been reduced to a scattering of reservations struggling for identity and survival. Many had chosen to adopt the ways of the whites, hoping in this manner to improve their situation. One such individual was Parker, who early in life determined to live and succeed in the white world.

Grant asked his aide Ely Parker, an American Indian of the Seneca tribe, to make a fair copy of the surrender agreement. According to historian Daryl Watson, Ely S. Parker was a Seneca Indian born in 1828 on the Tonawanda Indian Reservation in western New York. The Senecas were one of the tribes of the great Iroquois Confederation called the Six Nations. By the time of Parker’s birth, this once powerful confederation had been reduced to a scattering of reservations struggling for identity and survival. Many had chosen to adopt the ways of the whites, hoping in this manner to improve their situation. One such individual was Parker, who early in life determined to live and succeed in the white world.

When Lee ventured, “I am glad to see one real American here.” Parker memorably replied, “We are all Americans. “Grant would write in his memoirs “What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know.” His own feelings, which had earlier been jubilant, were now “sad and depressed.” He couldn’t rejoice at the downfall of a foe that had “suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse. “Now the door to the parlor was opened, and Grant’s officers were introduced to Lee, including “a newly minted captain, Robert Todd Lincoln, the twenty-one-year-old son of the president,” Mr. Guelzo writes.

Grant and Lee shook hands; Lee stepped onto the porch and signaled his orderly for his horse. An Illinois cavalry officer, George Forsyth, remembered every Union officer on the porch “sprang to his feet . . . every hand . . . raised in military salute.”

Lee looked to the east, where his army was in its last encampment. As he turned to leave, Grant came out to the steps and saluted him by raising his hat.

Lee reciprocated and rode off slowly to break the news to the men he’d commanded.

Mr. Guelzo: wrote: “He spoke briefly and simply to them, as if to a theater company after its last curtain.”

“They had done their duty,” Lee said: “Leave the result to God. Go to your homes and resume your occupations. Obey the laws and become as good citizens as you were soldiers.”

Grant had something Lee didn’t have. Lee couldn’t act under instructions of his government because it had effectively collapsed when Richmond fell.

Events had moved too quickly for Grant to receive specific instruction from Washington, but he knew the president’s mind. In the last year of the war, he and Lincoln had become good friends, and in their conversations,

Grant had been struck by the president’s “generous and kindly spirit toward the Southern people” and the absence of any “revengeful disposition.”

Days before the surrender Lincoln had visited Grant’s headquarters at City Point, Va. The president spent a day at a field hospital, where in “a tender spirit of reconciliation” he “shook hands with wounded confederates,” in Mr. Chernow’s words. A Northern colonel who described Lincoln as “the ugliest man I ever put my eyes on,” with an “expression of plebeian vulgarity in his face,” spoke with him and found “a very honest and kindly man” who was “highly intellectual.”

The mercy shown at Appomattox is a kind of golden moment in American history, but history’s barrage didn’t stop. America exploded with excitement at the end of the war, and all Washington was lit with lights, flags, bunting.

On Good Friday, April 14, Lincoln met with his son Robert to hear of what he saw at Appomattox, and then with his cabinet, including Gen. Grant, where he happily backed up Grant’s generosity. Grant, he said, had operated fully within his wishes.

Lincoln was assassinated that night, died Saturday morning, and for a long time the next day would be called “black Easter.”

But what is the meaning of Appomattox? What explains the wisdom and mercy shown? How does a nation do that, produce it?

As you see these past weeks, I have been back to my history books. You learn a lot that way, not only about the country and the world and “man,” but even yourself. “Would you have let your enemy go home in dignity, with the horses and guns? And not bring the law down on their heads? And the answer—what does that tell you about you?

All of the above, appeared in the April 16, 2022, print edition of the Wall Street Journal. The article was written by Peggy Noonan.

For the Author of “THE LADIES OF THE SETTERS LAKE” just to continue with our story and ignore all other members of the McLean family, especially the wife. would be ludicrous and, an unforgivable character violation of what this writing is all about, THE VIOLATION OF THE BASIC RIGHTS OF WOMEN, especially those with domineering husbands.

For the Author of “THE LADIES OF THE SETTERS LAKE” just to continue with our story and ignore all other members of the McLean family, especially the wife. would be ludicrous and, an unforgivable character violation of what this writing is all about, THE VIOLATION OF THE BASIC RIGHTS OF WOMEN, especially those with domineering husbands.

The entire McLean family, including his young wife, a widow, named Virginia Mason McLean are sitting on the front porch with their two children and a slave in this very early photograph of the McLean house, in which the Civil War ended.

Mrs. Virginia Beverley Hooe Mason was born on May 28, 1818. Her first husband was Dr. John Seddon Mason. He married Virginia Beverley Hooe on November 12, 1839. Dr. Mason died on June 24, 1850, apparently from natural causes. No other reason is given.

Doctor Mason left Virginia financially well off, and owner of several properties. Wilmer McLean was rumored to be aware of that and was openly criticized for marrying Virginia Mason, for that reason.

On April 9, 1865, the war revisited McLean. Confederate General Robert E. Lee was about to surrender to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. He sent a messenger to Appomattox Court House (again, this is the name of the town) The messenger knocked on McLean’s door and requested the use of his home, to which McLean reluctantly agreed. Lee surrendered to Grant in the parlor of McLean’s house, effectively ending the Civil War.

As soon as Grant left the McLean House, a souvenir craze swept over the Federal officers who were present at the surrender. Maj. Gen. P. H. Sheridan is supposed to have paid $20.00, two 10.00 gold coins, for the table on which Grant drafted the terms of the surrender.

Even though McLean made some money during the war by renting out his house and much more running sugar for the Confederacy, he had little to show for it after the war. McLean was paid entirely in Confederate notes — a currency that no longer existed after the fall of the Confederacy. In 1865, his house was foreclosed on. After losing the house and having very little money to his name, McLean moved his family back to Alexandria, Virginia. There McLean lived out the rest of his life as an IRS auditor.

Even though McLean made some money during the war by renting out his house and much more running sugar for the Confederacy, he had little to show for it after the war. McLean was paid entirely in Confederate notes — a currency that no longer existed after the fall of the Confederacy. In 1865, his house was foreclosed on. After losing the house and having very little money to his name, McLean moved his family back to Alexandria, Virginia. There McLean lived out the rest of his life as an IRS auditor.

He retired at the age of 66 and passed away two years later.

And why did the Author spend so much time on the Civil War? Because it was THE war for David Rhodes and the Rhodes family, including Bessie with the red hair. And David, for the wiggle of his toe. The second and first World Wars and the forgotten “one” the Korean War, also are featured.

Other than the Essons, all the rest of our families that ended up in Kansas, came from New York, Ohio, Illinois or Indiana. Most, if not all, were responding to being military veterans of the Civil War. As our story unfurls you will be introduced to all of them.

Other than the Essons, all the rest of our families that ended up in Kansas, came from New York, Ohio, Illinois or Indiana. Most, if not all, were responding to being military veterans of the Civil War. As our story unfurls you will be introduced to all of them.

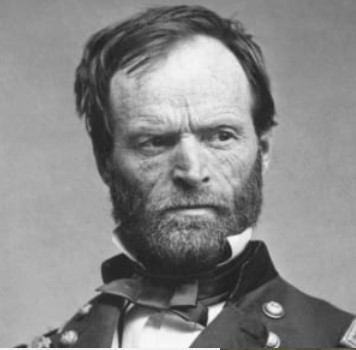

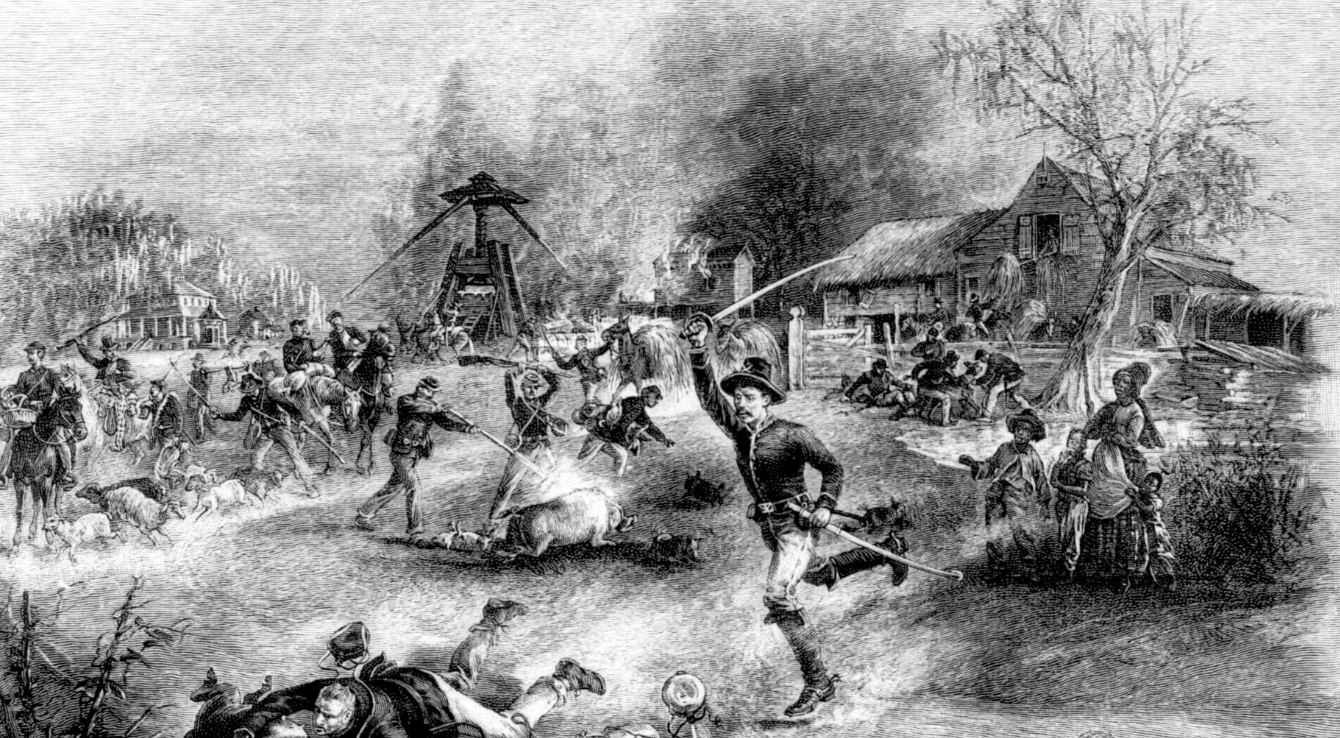

Let us hope our families are thru with them, and events like the Union General Sherman and his awful March to the Sea that still haunts the South, and events like Pearl Harbor, and all the other tragedies, of man and the natural ones.

As Anne Bailey said in her article for the New Georgia Encyclopedia, Confederate president Jefferson Davis had urged Georgians to undertake a scorched-earth policy of poisoning wells and burning fields, but civilians in the army’s path had not done so. Sherman, however, burned or captured all the food stores that Georgians had saved for the winter months. As a result of the hardships on women and children, desertions increased in Robert E. Lee’s army in Virginia. Sherman believed his campaign against civilians would shorten the war by breaking the Confederate will to fight, and he eventually received permission to carry this psychological warfare into South Carolina in early 1865. By marching through Georgia and South Carolina he became an archvillain in the South and a hero in the North.

As Anne Bailey said in her article for the New Georgia Encyclopedia, Confederate president Jefferson Davis had urged Georgians to undertake a scorched-earth policy of poisoning wells and burning fields, but civilians in the army’s path had not done so. Sherman, however, burned or captured all the food stores that Georgians had saved for the winter months. As a result of the hardships on women and children, desertions increased in Robert E. Lee’s army in Virginia. Sherman believed his campaign against civilians would shorten the war by breaking the Confederate will to fight, and he eventually received permission to carry this psychological warfare into South Carolina in early 1865. By marching through Georgia and South Carolina he became an archvillain in the South and a hero in the North.