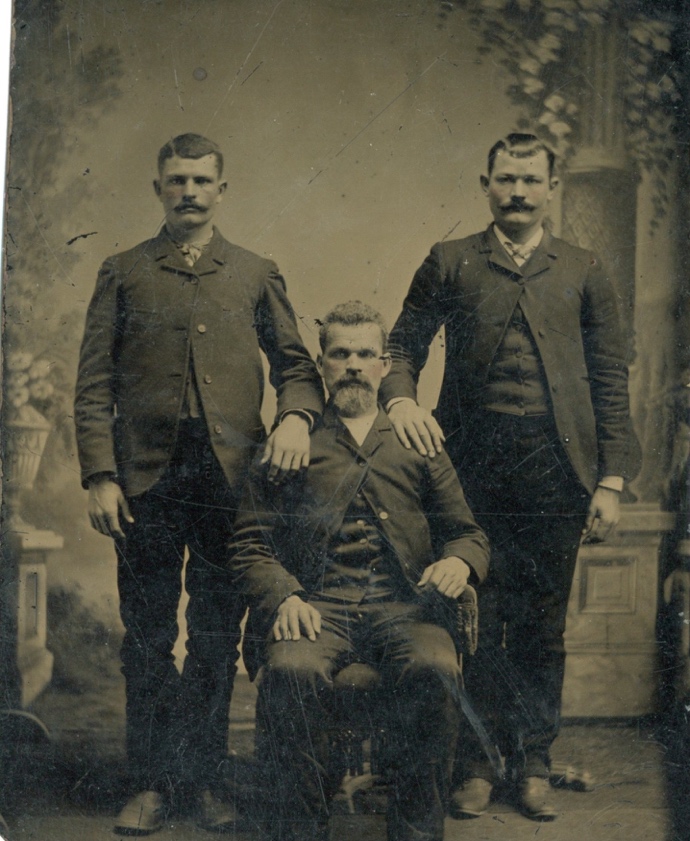

Often times we see pictures of our ancestors in their older years. For those born in the early eighteen hundreds, this is easily explained when you consider that most folks at that time did not have cameras. Many family photos took place as they poised in their black and white film world at the photographer’s studio. Most of our pictures of Leander, Jim and Bill find them older, particularly Leander and fatter for Jim and Bill. But see below how they looked when all were in their prime.

Leander and his sons grew some of Kentucky’s finest tobacco. They operated earth moving equipment, mostly powered by early crude steam engines and animals such as seen in the picture below. It was hard work, as was all farm work then, but these two healthy young men helped their father. Remember in the first part of our story, the forward, we spoke of our efforts to highlight the lives of our ancestors, and the element of why was given so much importance. Perhaps the skullduggery of the big tobacco companies played a role in causing Leander to leave the farming of tobacco. The horrible depression of 1983 also must have played a role.

This picture of the three, Jim, Leander sitting, and Bill was taken in Kentucky, before 1888, as the three worked together in construction and farming.

Growing tobacco without power equipment was hard work as was all of farming in those days and some of the biggest Tobacco Companies began a reduction in how much they would pay the farmers for their tobacco. This process began slowly at first, in the middle eighteen-nineties culminating in large scale violence by some of the tobacco farmers. Earlier in our writing it was pointed out how we seldom were aware as to why our earlier ancestors did things. Leander, Jim and Bill were involved in growing the Burley tobacco. As shown above, it was hard work and the profit was already slim. Coercion among the large tobacco processing companies for the sole purpose of cheating the farmers was met with widespread objection and oftentimes violence. Leander could see the problem getting worse and by the early nineteen-hundreds, so did Jim. Leander and Bill were already in Tennessee. We have wondered what would cause the Setters clan to leave Kentucky in the first place, now we probably know.

The picture above where a mule is used and the picture below with a tractor putting the mule out to pasture could be reasons for getting out of the farming business.

Burley farmers formed the ASE, the American Society of Equity, a.k.a. “The Equity,” to oppose the tobacco trust. In 1908, the Falmouth Outlook and the Boone County Recorder both ran a weekly ASE “society” column to keep readers up to date on ASE activities. The Owenton News-Herald ran weekly front-page stories for months supporting the ASE and the Carrollton Democrat urged farmers “Don’t raise tobacco; raise hell.” The Equity decided to raise no crop in 1908 and, was mostly successful in that effort. It’s believed that Bracken County in 1908 didn’t have a single stalk of tobacco come out of the ground. At least one source says Owen County, too, did not grow a single tobacco plant in 1908.

Burley farmers formed the ASE, the American Society of Equity, a.k.a. “The Equity,” to oppose the tobacco trust. In 1908, the Falmouth Outlook and the Boone County Recorder both ran a weekly ASE “society” column to keep readers up to date on ASE activities. The Owenton News-Herald ran weekly front-page stories for months supporting the ASE and the Carrollton Democrat urged farmers “Don’t raise tobacco; raise hell.” The Equity decided to raise no crop in 1908 and, was mostly successful in that effort. It’s believed that Bracken County in 1908 didn’t have a single stalk of tobacco come out of the ground. At least one source says Owen County, too, did not grow a single tobacco plant in 1908.

But some farmers refused to boycott, frustrating more ardent coalition members, who resorted to violence. For two years, beginning in 1905, masked men known as “Night Riders” raided communities around the state. They burned buildings and destroyed fields and machinery in order to coerce hesitant farmers into joining them. Their night-time raids found them looking a great deal like KKK night riders, but as a character in Robert Penn Warren’s first novel, Night Riders, noted, “the good Lord never got any thousand or so men together for any purpose without a liberal assortment of sons of bitches thrown in.”

In 1880 Kentucky produced 36 percent of the total national tobacco production, and was first in the country, with nearly twice as much tobacco produced as by Virginia, then the second-place state. Later the type became referred to as burley tobacco, which is air-cured.

An ad in the local paper in Boone County in the middle eighteen-eighties cited Leander’s tobacco farm:

“Leander Setters, who lives down on Gunpowder, estimates his last year’s crop of tobacco at 40, (XH» pounds. He would like to be interviewed by a few buyers about this time of the year.”

. Burley tobacco won acclaim for holding the sweeteners popular in plug tobacco at the time. Plug tobacco was the most popular tobacco product until World War I, when blended cigarettes took its place. Leander chewed the plug tobacco and smoked his pipe almost to the time of his death at the age of ninety-two.

By the time the entire Setters family was gone from Kentucky, and Leander’s pipe no longer lit, tobacco found disfavor in America and it began the long road to being all but denied to smokers. Opponents of the habit maintain that each year more than 8,000 Kentuckians die of illnesses caused by tobacco use. Some die of lung cancer, while others fall victim to cardiovascular disease.

Recently the State of Kentucky began the process of asking farmers if non-smoking signs could be painted on old tobacco barns. As shown below, the message can be very noticeable.

The murals cost between $12,000 and $20,000. Farmers are paid between $600 and $1,000 and agree to leave the mural up for five years. A few farmers are now enjoying the added, but small, income. Note in this picture there is no tobacco in the old tobacco barn……just bales of hay.

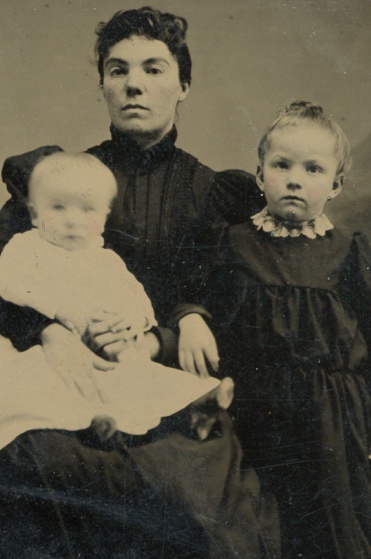

When Leander and Bill moved from Boone County down to Nashville and onto Little Marrowbone, Jim and Carrie had a one-year old daughter, Bertha, and were four years away from having a son, John. Carrie, a stern-faced mother is shown with the two in November of 1892. John was born on July 5th of that year. For them then, moving was not an option.

A few pages back, remember the phrase, “and so did Jim”?

Just when Jim and Carrie made their decision to move down to Tennessee and Little Marrowbone is not known. It may have been that Jim was still raising Burley Tobacco too. The issue with the big tobacco companies was getting very ugly. People were dying. Jim had a fourteen-year-old son and a seventeen-year- old daughter in 1904, and the family was not getting any younger. And Jim had reached the age of forty-six. His dad had moved to Tennessee at the age of forty-eight. So, for him, it was now or never.

Just when Jim and Carrie made their decision to move down to Tennessee and Little Marrowbone is not known. It may have been that Jim was still raising Burley Tobacco too. The issue with the big tobacco companies was getting very ugly. People were dying. Jim had a fourteen-year-old son and a seventeen-year- old daughter in 1904, and the family was not getting any younger. And Jim had reached the age of forty-six. His dad had moved to Tennessee at the age of forty-eight. So, for him, it was now or never.

Letters from his brother Bill and his father Leander painted a nice picture of how things could be down in the hills of Tennessee. There was even a nice write-up in the local paper about his brother and his father. Jim’s mother, Louisa, had been dead for fourteen years. His dad had remarried the Jones lady who had been helping take care of Louisa. That did not surprise Jim.

Jim’s sister, Sarah, had died in 1878 at the age of twenty. We don’t know why such an early death. But he had Carrie and two teen-aged children to be cared for.

By the time the family got things ready for the move though, his daughter, Bertha, was involved with a young man. Bertha remained in Kentucky until she gave birth to her baby boy.

When Jim was twenty-two years old more than fifty people died in the city just across the Ohio River, Cincinnati, in riots brought about by a jury verdict in a murder. It was of the most destructive riots in American history. In an attempt to lynch the man who did the killing of another, the courthouse was destroyed. That and the tobacco grower’s problem, plus the ongoing financial depression across the country, also may have played a role in Jim’s decision.

And Jim might have just missed his father and brother. His mother, Louisa, had been dead for fifteen years.

A picture of Bertha, her baby James Lloyd, Carrie and Carrie’s mother, Elzie (Riddell), bring a bit of mystery to the family’s gatherings. We know the baby was born in Kentucky in 1908, but the presence of Carrie with her mother means that either Bertha traveled to Nashville or Carrie visited from Nashville. A dark cloud awaited Jim’s first grandson.

Bertha became a mother at the age of 21. At the age of 33 the opposite would occur. James Madison Setters, the Jim we are talking about, Leander’s son and Bertha’s father, would live to see his own son suffering through the trenches of France in a horrible war.

His three grandsons would take part in another World War one of them taking part in two other wars. Wars in which half a million of our military men would die. A great-grandson would be in a nuclear submarine cruising through murky harbors of the Soviet Union in a cold war; but they all came back home. But this little baby would meet his fate in Jim’s own front yard. We’ll delve into that tragedy later in our story.

The author of this story, Jim Setters, is anxious to reiterate that the Jim above is HIS grandfather and not the author.

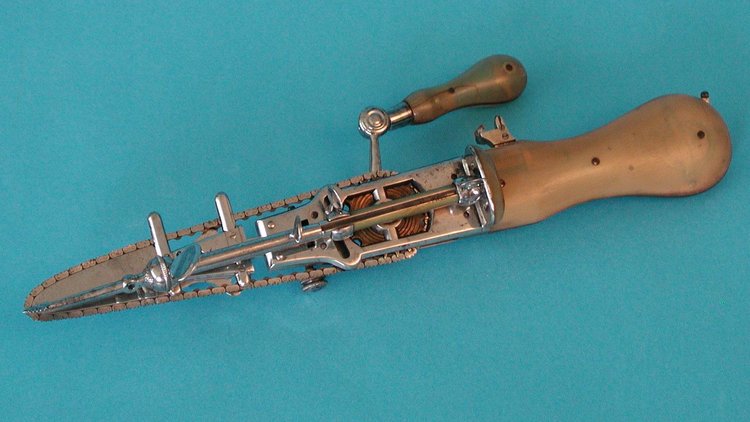

It is a relatively simple process in modern times to cut down trees and haul the logs out of the forest, mostly because of the gasoline engine. But, when Leander and his men began the task, there were no chain saws, no tractors; except those bulky things that were steam engine powered.

We mentioned in our story somewhere about one of Leander’s great-grandsons finding a shoe for an ox, but more than likely Leander’s men used mules. And, more than likely the cross ties, that were chiseled out where the tree fell with what was called a broad-axe, were drug, or as they called it, snaked out to a clearing to be loaded onto wagons. Either way, it was torturous work.

Incidentally, the first use of a chain saw was to help women have babies before cesarean surgery came about. The word cesarean was based on the ancient story Julius Caesar was born that way. Research shows that he was not since his mother was still alive well into his life. In ancient times, only babies were so removed after the mother was dead. If not dead already, the surgery did it.

You’re probably already clenching your knees together after reading the title, but yes, the chainsaw was originally invented to assist in childbirth. When babies couldn’t fit through or they would get stuck in the pelvis, parts of bone and cartridge were removed to create more space for the baby. This is called a “symphysiotomy”.

Still, anything with the word chainsaw, knife, saw, or blade coming at your downstairs in a completely conscious surgery is terrifying! Here is the first surgical chainsaw used for those symphysiotomies.

Still, anything with the word chainsaw, knife, saw, or blade coming at your downstairs in a completely conscious surgery is terrifying! Here is the first surgical chainsaw used for those symphysiotomies.

The chainsaw was soon used for other bone cutting operations and amputations in the surgical room. It then evolved into a woodworking tool when people noticed how quickly and easily it was to get through, well, anything. It became larger and more powerful and eventually grew to be the monster we know today. It wasn’t until about 1918 however before the gasoline engine was used for power, a quarter of a century before Leander began working in the woods on Little Marrowbone creek.

Picture taken after Leander’s great-grandson Jim recovered the Lake and built a house on the shore of the Lake.

Picture taken after Leander’s great-grandson Jim recovered the Lake and built a house on the shore of the Lake.

This picture of the front of the old Setters/Winters home would be an image of what it once was when it was built in the middle eighteen hundreds. The road is much different, higher than the one roughed in by wagons and scoops, but the design of the structure is the very same, because it is the very same building. The overhead electric and telephone wires, appearing faintly overhead, were added a hundred years after the house was built. Leander’s great grandson Jim built the little structure to the left and across the road from his great-grandfathers old house about a hundred years after Leander moved into the house from Kentucky.

A view in June of 2017 of the back of the old Setters home shows little change in the way it looked when Leander and Louisa moved into it in 1888, one hundred twenty-nine years earlier. The rocked room to the left was actually just a porch until Don and Sherrill Evans close it in. The driveway is the same, not paved. The creek is to the right of the home and down a slight creek bank where the three-hole outdoor privy was located. The feces would simply pile up under the open side of the little outhouse and when heavy rains happened, the creek rose and washed all of the evidence away. This procedure, and its ramifications, is covered in another portion of this story.

A view in June of 2017 of the back of the old Setters home shows little change in the way it looked when Leander and Louisa moved into it in 1888, one hundred twenty-nine years earlier. The rocked room to the left was actually just a porch until Don and Sherrill Evans close it in. The driveway is the same, not paved. The creek is to the right of the home and down a slight creek bank where the three-hole outdoor privy was located. The feces would simply pile up under the open side of the little outhouse and when heavy rains happened, the creek rose and washed all of the evidence away. This procedure, and its ramifications, is covered in another portion of this story.

Also, not shown here is the log smokehouse that sat just twelve feet or so, in back of the house. The Evans moved that up the little creek where it still sits near a year ‘round spring near some beautiful waterfalls.

Leander became a widower at the age of fifty. Leander would live more than forty more years, but not alone. Even though Leander’s son Bill and his wife Sallie had come to Little Marrowbone with his father they brought along a live-in housekeeper/ care giver for Louisa. She was Aletha Jones, soon to become Aletha Setters. Folks called her Leethy. Aletha was born in Boone County Kentucky, in 1855, two years before Leander and Louisa were married and, the year that Abraham Lincoln lost the election as a candidate for the U. S. Senate. She was ten when Lincoln, as the president, was assassinated

She was thirty-five years old when she and Leander married, October 26th, 1890. Aletha’s husband had died in the late 1870s leaving her with three children and living in the home of her sister. One of her sons was named Robert. He was twelve years old when she married Leander. Soon after Leander died in 1932, the Conchin’s family moved into the old Setters home. What happened to her children after she married Leander remains, at least at this writing, a mystery, although one of her daughters was eighteen, the other seventeen in 1890.

He had buried Louisa just three months before he and Aletha were married. Those who knew them were not surprised. Alice Setters, Leander’s daughter-in-law, tells of stories about Leander and Aletha removing the wheels from Louisa’s wheelchair in order to keep her from being mobile a few times. Was this to lessen Louisa’s chances of being injured or prevent her from being aware of certain activities in the house? We’ll probably never know. After all, this sort of thing is not something that a little sophisticated white-haired lady would want to embellish in much detail. On the other hand, it is one that she could not totally ignore either. When Alice would relate the incident her facial expressions would be the vehicle, not necessarily the wording.

“Leethy” was to be his wife for thirty-nine years. Louisa had shared his life for thirty-three. Aletha died August 8, 1929, four months before the murderous Joseph Stalin became the dictator of Russia. She is buried in the cemetery at Bear Hollow and Clarksville highway. Her tombstone is about three miles from Louisa’s. Louisa’s tombstone sits next to Leander’s’.

Aleatha died August 8, 1929, four months before the murderous Joseph Stalin became the dictator of Russia. She is buried in the cemetery at Bear Hollow and Clarksville highway. Her tombstone is about three miles from Louisa’s.

Forty years earlier they shared the same house, the same man. There are those rumors. Aleatha was not admired by Leander’s survivors and when Leander died his grave was placed next to Louisa’s in the little cemetery on Little Marrowbone, in the shadow of the old home place and within a stone’s throw from the lake. The tombstone of his son, James, was also already there.

Leander wrote his will fifteen years before his death when he was seventy-seven years old. At that day and time, he had waited, based upon expected lifetime of the American male, what many, thought was almost too long. At age seventy-seven he had already lived longer than any member in his family history. He asked that a plain and substantial monument be erected at his grave.

There are what we would call home-made grave markers at this little cemetery that sits beside and across the road from the old Setters home. But these three are the only ones with the names of Setters. Leander on the left, Louisa in the center and Jim, their son on the right side of the picture. All the others are of the Winters family or perhaps some children of others who had lived in that house. To the left of Leander’s stone is an odd shaped one and to its left is the marker of Catherine Winters. You will learn more about that stone but little about Catherine later.

Jim’s wife Carrie was buried in Kentucky as was their son John. Jim and Carrie’s daughter, Bertha is buried in Nashville. One of their grandsons, James Lloyd, is buried in Kentucky. Another grandson of Jim and Carrie, Harold – John’s son – is buried in Louisiana. Bertha, who made sure that Aletha was not to be buried next to her, Bertha’s, grandfather.

One of Leander’s great-grandsons, Harold, is buried in Louisiana, and like Leander, is buried next to his first wife, Jamie, who died about fifteen years before Harold. When Harold died, he was married to Vera, but she lived until 2010 and was buried in Pawnee, Oklahoma. We will probably never know for sure who made those final burial decisions, except with Leander, it was strongly assumed to be Bertha, his granddaughter.

Notice the lantern and the fencing that surrounds the graves of Leander, Louisa and their son James. As you stand there and look at their small monuments, then turn around, this is the rest of the story. Leander’s great-grandson James Robert Setters and his wife Dana built this, landscaped it and rebuilt the lake. All of it was completed just fifty years after Leander was buried.If you look over the top of Leander’s tombstone you will see several smaller less sophisticated grave markers. The grave markers of Leander, Louisa and Jim are not the first ones on that little plot. The others are adults and children of the Winters family. Also not shown is the grave of Catherine Winters. We’ll tell you about that later.

That monument, actually just a simple two-foot high tombstone, along with Louisa’s and their son Jim’s, is now in the small cemetery in the front yard of the home at the lake site, only a couple of hundred feet from where Leander stood in a 1908 photograph as he supervised men scooping the mud out of the lake which took place a few months after, the then, President Teddy Roosevelt came to Nashville to visit the Peabody college. Just to emphasize the difference in the culture at that time, there is a picture of his entourage leaving the school escorted by two men on horseback in Confederate Army Uniforms. They were members of the honorary Confederate Civil War Veterans honor guard in full Civil War uniforms. Escorting the President of the United States? One can only imagine the uproar should a scene take place like that now, a hundred years later. Leander probably knew little about Roosevelt’s visit.

Nashville was a busy city in 1908. A bit confusing to the naked eye and to the camera. These scenes taken in 1908 shows the mixture of animals and early cars. A bit confusing and disarranged but very busy.

When Leander began cleaning the mud out of the lake, we take note that just two months earlier, Henry Ford introduced the first Model T. In another three years a fellow by the name of Louis Chevrolet began building cars. The Chicago Cubs baseball team, in 1908 had just a few days earlier won the World Series. In fact, The Cubs won back-to-back World Series championships in 1907 and 1908, becoming the first major league team to play in three consecutive World Series, and the first to win it twice. When Leander began re-filling the lake though, the Cubs began a one hundred and eight-year world series famine. They played in a few, but it was not until 2016 that they won the series again. Less than a week later the first woman was almost elected president of the United States.

In our modern times a collection of automobiles such as you see above would not be unusual. What IS unusual about those in this picture is they all look alike. Can you imagine concluding a long day of picnicking, swimming and then at dusk trying to find your car in this mess. Them wuz the good ole days.

Since there was no radio and TV in 1908 and the newspapers didn’t get down to Little Marrowbone very often, what the Chicago Cubs did or did not do was probably of little interest to Leander and the guys on those mules dredging out Setters Lake. They probably even knew little about the Nashville baseball team named that year as the Nashville Vols, nor that their big baseball diamond was named the same year as the Sulfur Dell.

Speaking of names, a year before those mules began pulling the scoops, a baby was born in Winterset, Iowa. The name on his birth certificate was Marion Robert Morrison. We now know him as John Wayne, the movie star. He looked exactly like this the year that one of Leander Setters Great Grandsons’ wife, Dana Chapman, was born. She also was born in Iowa, 150 Miles away from Winterset.

News came slowly and seldom down into the hills. The time that elapsed from when the first scoop of gravel began the lake and men with shovels dug his grave were twenty-four years that most of us would be pleased to experience. Maybe not the final two or three.

Less than two months after Aletha died the Stock Market completely collapsed on what is now referred to as Black Tuesday. The great depression was on its way. Leander again became a widower. But not for long. He died three years later, April 3, 1932 at the age of ninety-two years and two months. He died 12 days before Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced he would run for the office of president of the United States. and one day, one month and one year before Roosevelt was sworn into that office. The great depression had already begun. Unemployment was now at over twenty-three percent. The population of the United States was just a little over ninety-one million. Of this, twelve million, or twenty-three percent of the work force, were unemployed.

The hills that Leander owned were virtually without since been unable to pursue or even maintain what at one time had been a prosperous business. Leander’s life was finished, just eight years shy of a century. Within five years, from 1926 to 1931, Leander had buried his second wife, both of his sons, a daughter-in-law and his sister Harriett had died in Arthur Illinois. Harriett had married when she was sixteen and was mother to twelve children. She was eighty-one. All of the deaths were from heart failure.

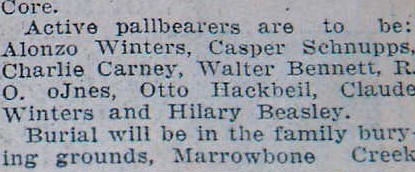

Leander died eight months after his son James was buried. And at the age of ninety-two, one would assume he had no old friends still alive. But, all of his active pall bearers, the ones carrying the casket, were old cronies who lived within three miles. He had lived amongst them for forty-four years. The honorary ones included a judge and four doctors.

Leander died eight months after his son James was buried. And at the age of ninety-two, one would assume he had no old friends still alive. But, all of his active pall bearers, the ones carrying the casket, were old cronies who lived within three miles. He had lived amongst them for forty-four years. The honorary ones included a judge and four doctors.

Only one of these active pallbearers, Hilary Beasley, was not known personally by Jim, Leander’s great-grandson.

More than likely some had met Leander while enjoying the amenities at Setters Lake. Bertha had admitted her grandfather to the Davidson County care home, also known as the poor house, shortly after James, her father, died. Leander had been in the hospital bed for seven months before he passed away. Leander left very little; a small monument and the lake. A final settlement was paid to his granddaughter, Bertha, five years after his death. The check was in the amount of $63.27.

The majority of people in the United States were not aware of what was going on in the early thirties in the Pacific, but the Japanese empire was already beginning to seek an expansion of its Navy. The Japanese wanted equal footing with the United States and England in naval strength. President Roosevelt, who would later label December 7, 1941 as a date of infamy, played an important role in denying the Japanese the strength. Just an observation about the times. Two years after Leander was buried, Japanese warplanes killed over a thousand Chinese civilians, but we were busy with our depression and few people noticed.

We don’t have a picture of the house, in Kentucky, where Leander was born in 1840, but we do have a picture of the house, northwest of Nashville’s city limits, where he lay in his casket, ninety-two years and a couple of months later. Several of his relatives and friends gathered in this house on April 5th, 1932. And it is still there. Now, all of Davidson county is Nashville, Tennessee. There are no city limits. The change came thirty years after Leander’s death.

It was the home of Bill and Sally Setters, Leander’s son and daughter in law on what was then called the Hydes Ferry Pike and Drakes Branch. The Pike is now known as the Ashland City highway. The open casket was to be ready for viewing at 10:30 that morning. Sally was there, but Bill had been dead for six years. Shortly after the casket was opened and proper remarks were made, one of Leander’s great-grandsons, four and a half year-old James, walked up and looked into the casket.

It was the home of Bill and Sally Setters, Leander’s son and daughter in law on what was then called the Hydes Ferry Pike and Drakes Branch. The Pike is now known as the Ashland City highway. The open casket was to be ready for viewing at 10:30 that morning. Sally was there, but Bill had been dead for six years. Shortly after the casket was opened and proper remarks were made, one of Leander’s great-grandsons, four and a half year-old James, walked up and looked into the casket.

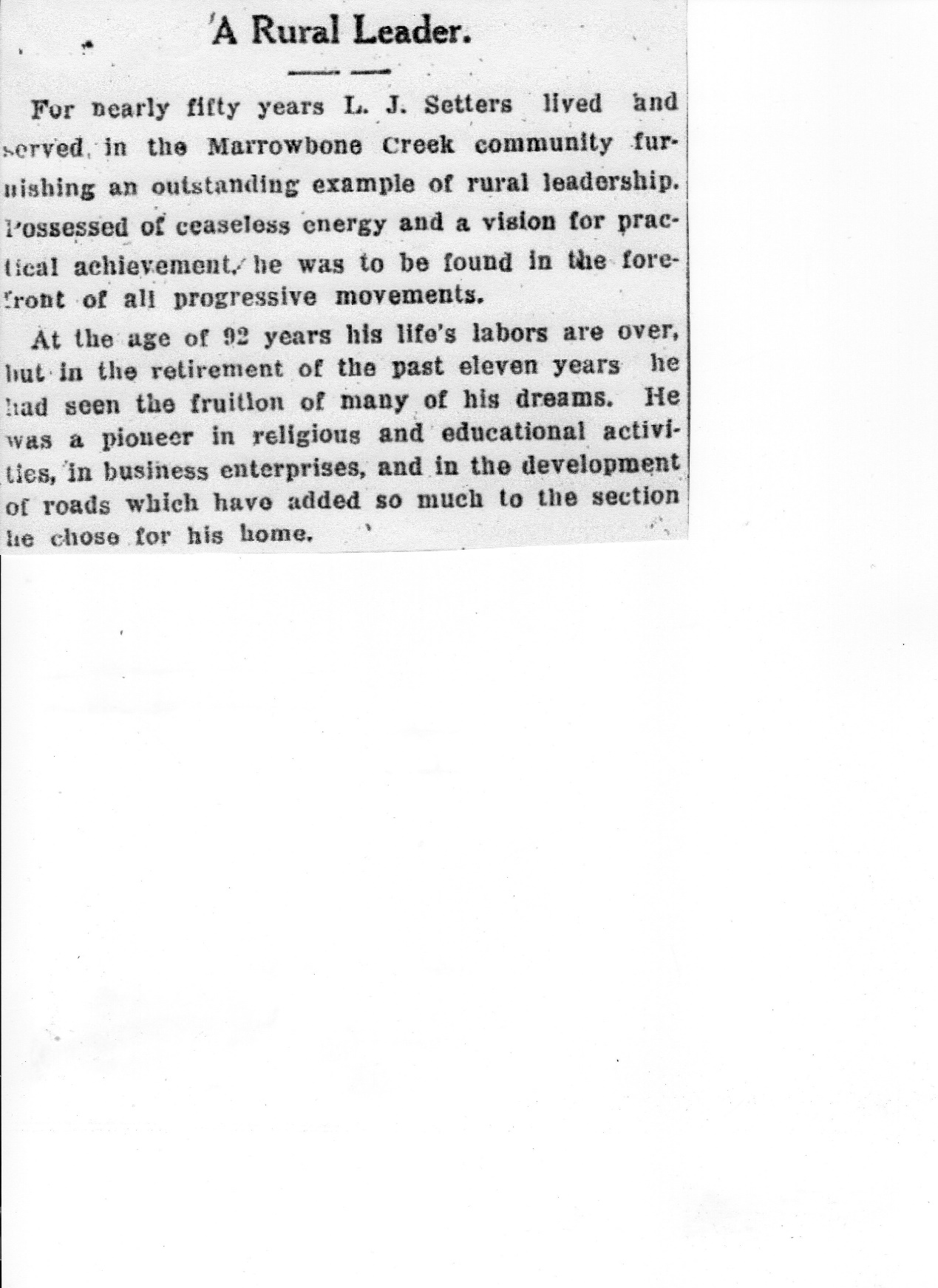

At that point in time and in his life, the little boy had no idea he was looking into the face of a near Legend. Below is a tribute written and published by the Nashville Tennessean that accompanied Leander’s obituary.

At that point in time and in his life, the little boy had no idea he was looking into the face of a near Legend. Below is a tribute written and published by the Nashville Tennessean that accompanied Leander’s obituary.

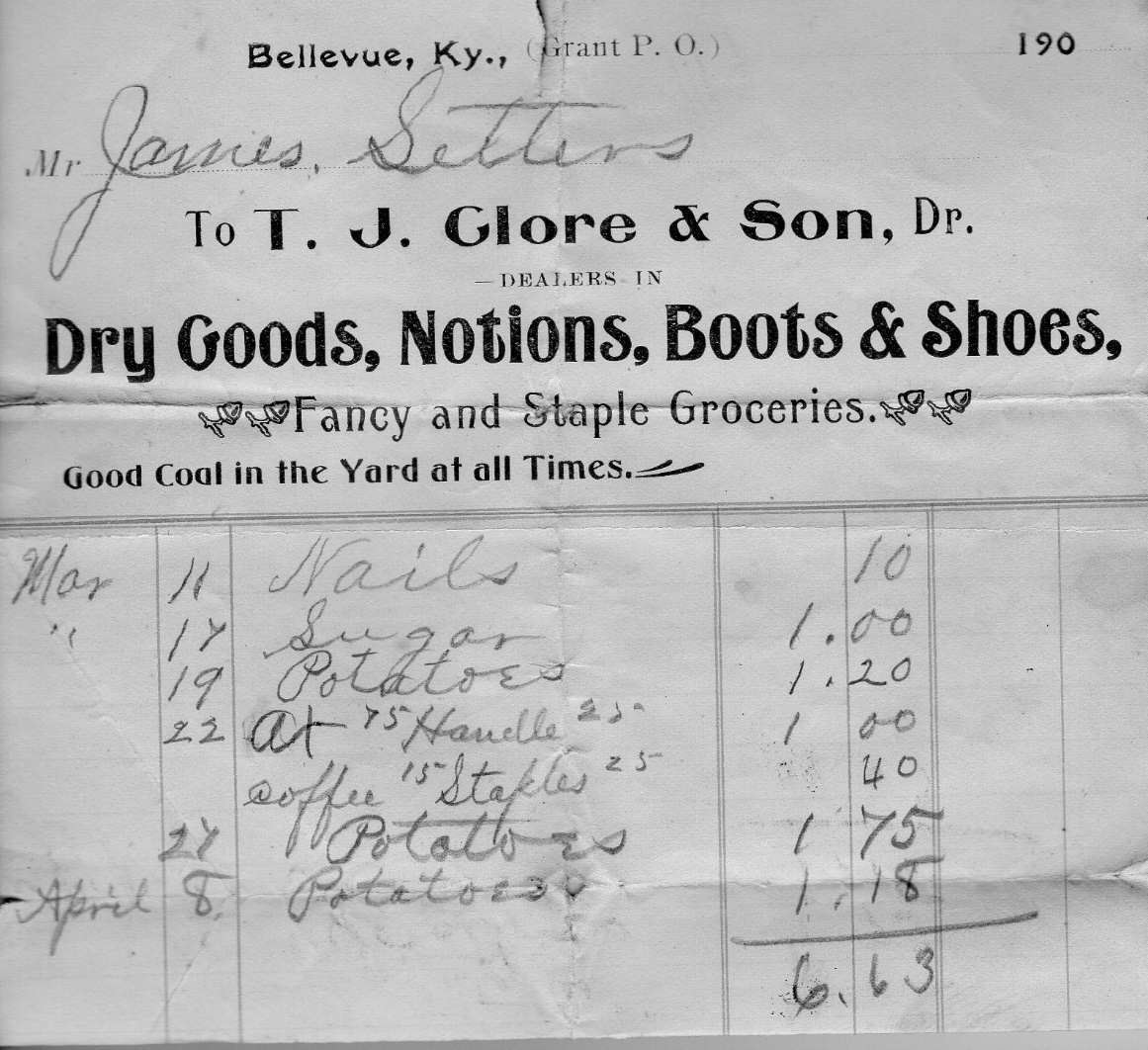

When Raymond was about ninety-years of age he gave to his brother Jim, the author, a collection of receipts that were part of their Grandfather’s belongings. There were many receipts, some dating as far back as the late eighteen-hundreds for purchases that their grandfather had made. This one is just an example.

There were much bigger ones too. Many for large equipment that James used in his work in the area in Kentucky. He did a lot of threshing and plowing for the farmers in the area.

Inside the box of receipts and other bits of legal matter was a little notebook, one like you would carry in your pocket. Some of its entries dated back beyond the adult life of John and maybe even to Leander. But it appears as though most of it were surveying entries made by John. John did a lot of surveying in the area and was even assisted much of the time by his two sons, Raymond and Jim. John would set up the surveying instrument. Jim would then keep the cross hairs on his Dad’s back while John used a big hacking blade to chart his way through the woods. When he strayed off course a bit, Jim would yell “RIGHT” or “LEFT.” John would drag a one hundred- foot long wire. Raymond would sit and wait for the end of the wire to come by and when it did, he yelled “LINE.” He would then get up, go up to his Dad, sit, and John would hack ahead and drag the long wire.

The procedure was somewhat basic, but it got the job done.

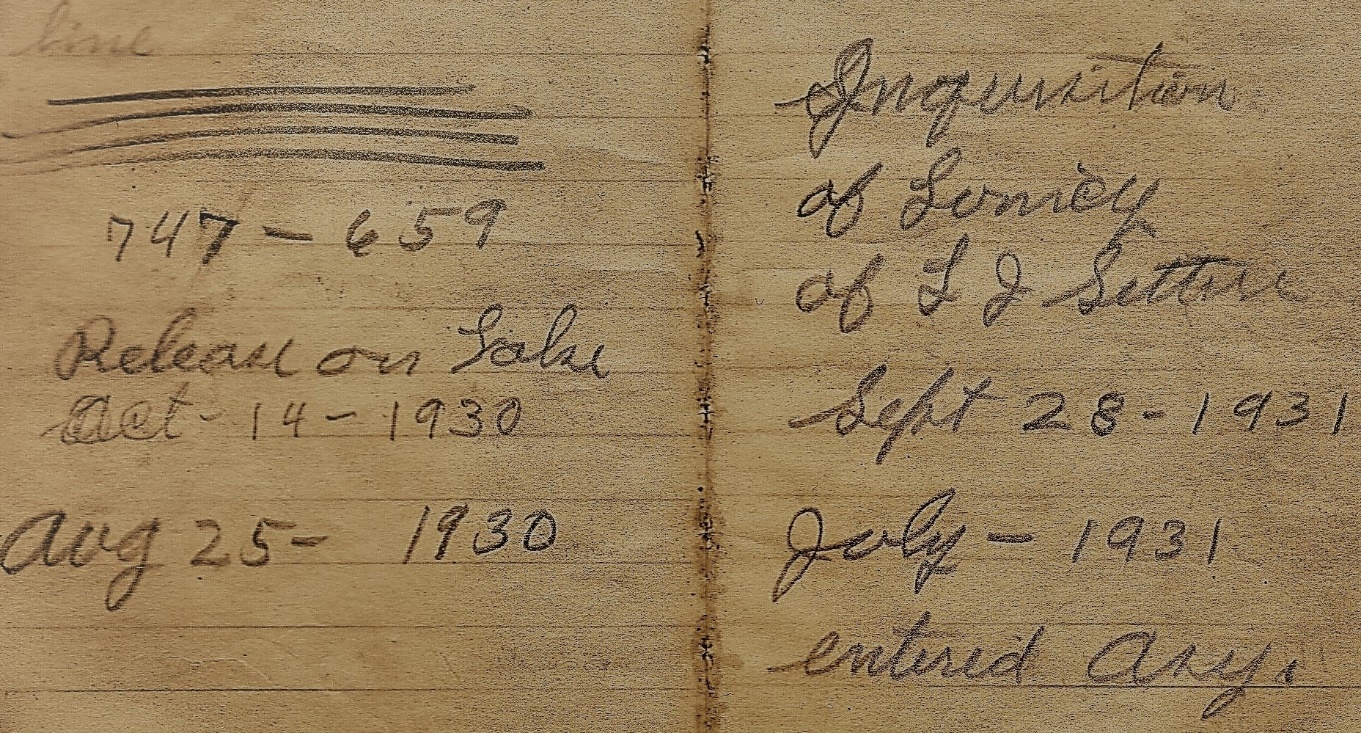

But in this book were the following entries. When Jim was ninety-one years old, he found them in the little notebook. They seemed to, in just a few words, spell the ending years of Leander. Surely John entered them. Who else would?

John and Bertha’s dad died in July of 1930. Their uncle Bill had died four years earlier. John and Bertha became owners of the lake. Leander died in April 1932.

He was committed to the asylum in July 1931. His LUNACY inquisition was held on September 28, 1931. It was how, at that time in our culture, we dealt with Alzheimer’s. It was called being feeble minded.

Did the Leander Setters empire collapse because of the depression, a cultural change in the area or had it just run its course? There is no way of knowing. Those who do know are no longer with us. And nothing is written down. One thing is certain though, Leander left Kentucky when the United States was in the grip of the worst economic depression it had ever experienced.

Just five years after he left Kentucky, thousands of other desperate people responded to the big land rush in Oklahoma. Leander’s work in northern Kentucky had been hard hit. And surely, he was aware of the fraud and overbuilding by railroads in America and even more tragic, ones in Great Britain. Grain and cotton prices fell by more than a third, wiping out many farmers, some of whom had employed Leander and his son James. That era was known as the Great Depression until the one that began in 1929. That one was even worse, and it helped to bring Leander’s downfall. That, and his age. In 1932 the second great depression was going strong and Leander was taking his final breath.

Two of those things were two too many. The loss of two wives, both sons and the inability of younger family members to carry the torch turned out the lights at Setters Lake. But the little lake still held water. Leander, of course had no idea his little lake would still be there more than a century later and look  the way it does now.

the way it does now.

Leander’s passing was not a national event. His small body laid in a casket, at the home of his daughter-in-law, Sallie Setters. Lying there with his white beard, dressed in his only suit, a black dated one, he is remembered by his great-grandson Jim, who was five years old. His only memory of Leander. Jim was 87 years old when his first great-grandson was born. Leander was 87 years old when Jim was born. Jim held his great-grandson in his arms. Did Leander ever hold Jim? Possibly. But no one really knows.

There is no record of any Setters men or women before living to that age. Leander’s grand-daughter, Bertha, was eighty-four when she died. One of his great-grandsons, John Raymond, exceeded Leander. Raymond died at the age of ninety-three. One thing that Leander did not do and that was climb up into a tree at the age of eighty-one with a chain saw and saw off a low hanging limb. John Raymond did. Of course, Leander would have been eighty-nine years old before the motorized chain saw was invented, so even if he had wanted to and was able at the age of eighty-one, he couldn’t. That is not to say that Leander could not have climbed up into a tree like his great-grandson at the age of eighty-one, it’s just that he could not have brought along a yet to be invented chain saw.

Strange how things turn out sometimes. Aletha’s son Robert Jones had children, one of them a girl about the same age as one of Leander’s great-grandsons, Harold. Harold’s family still lived in the house across the road. Robert and his family inherited and moved into the old Setters house. As was earlier mentioned, for some strange reason, Leander’s will, leaving the place to Aletha, actually, upon Leander’s death, placed the property in the name of her children. For a while this girl, Dorothy Jones and Harold Setters were sweet on each other. This would have found Leander’s great-grandson and Aletha’s granddaughter at least holding hands for a while. Had this situation continued, it could have eventually joined a Setters and a Jones again; nearly half a century after Leander and Aletha started the arrangement in 1890; possibly a little before.

Actually, such another arrangement had already taken place. Aletha’s son Robert married the daughter of Leander’s half-sister Susan. Leander’s mother, who had remarried to Mr. Zornes in Kentucky had two children by him and one of them ended up just five miles from Leander where she had a daughter. It was this daughter that married Aletha’s son Robert.

But like so many of the ladies who lived in that house, young and old, Dorothy Jones played an important role. Her father, Aletha’s son Robert, never learned to read. An illiterate, who worked at a farm tool wooden handle manufacturing firm in Nashville, after dinner each evening (it was called supper in those days) would sit on the front porch in the swing with Dorothy. She would read him the newspaper, page by page. This did not go un-noticed by the Setters boys. Especially one. He too had the sweets for Dorothy, but he was far too young and, that quest was totally unnoticed by her.

Leander and Aletha’s time together must have been a loving three score because in 1917 Leander, at the age of 77, being of sound mind and memory, and recognizing the uncertainty of life and the certainty of death wrote his will, leaving her the home place, 160 acres of land, her choice of two cows from the cattle on the place, a horse and a buggy and all the money he had. Leander asked that a plain and substantial monument be erected at his grave.

As Leander was writing his will, the winds of another war, World War I, were looming for the United States. Leander never participated in any of the wars that raged during his lifetime, but the two big ones, The Civil and World War I played a big role in his life. This war had already begun in Europe. His will was signed in February 1917.

Congress declared war on Germany two months later. Leander was too old. So were his sons. But his grandson John was twenty-five and answered the call. He served in the tank corps with the Army. John suffered mustard gas injuries and never really got over his wounds. That war was titled, “The War to end all Wars”. But it didn’t. Three of Leander’s great grandsons served during World War II and a great-great-grandson in a submarine in the Cold War with Russia, half a century after Leander’s death.

Leander left the five acres or so, where the lake is now, to his two sons Bill and Jim. Of course, both had died before Lender did. It was soon transferred to Jim’s two children, John and Bertha. Bertha ended up owning the property but John and Esther, his wife, and three sons continued to live there. At no charge.

Leander had continued in the cross tie making business after Louisa’s death. His crews pursued a rather simple method of forming the ties from trees. Using cross-cut saws (a long saw with a man on either end) to fall the trees; then sawing them in proper lengths, and finally using big wood axes, called broad axes, literally chopping them into the eight-foot six inches long, seven inches wide timbers that held up the railroad tracks.

The chainsaw, as we know it today, was invented by a fellow in Germany, fellow named Herr Stihl, about thirty-five years after Leander moved to Little Marrowbone. When he filed for the patent, it was not known as a chain saw, they called it a tree felling machine. In 1888 Leander could not have found the chainsaw of any use anyway, he had no gasoline.

Leander and his son Jim also operated a couple of sawmills in the area. Others were also combing middle Tennessee woods for those near perfect hardwood trees, but Leander had over six thousand acres to choose from. All to himself. His obituary refers to his cross tie and lumber efforts. When you consider that the life of a typical railroad cross tie could be one hundred years and that the things weighed around one hundred fifty pounds, it’s easy to see why Leander and Jim decided to switch over to the lumber milling business. Of course, each cross-tie was soaked in creosote which gave them their long lives, but this was done by the railway companies, not the men who cut the trees. This, according to David Webb, director of the U.S. Creosote Council.

Hauling hundreds of cross ties out on the terrible roads on Little Marrowbone by animal drawn wagons must have been a terrible chore. Many years after Leander decided to go to Tennessee to get into the crosstie business, one of his great-grandsons, John Raymond found a funny shaped animal shoe.

He showed it to his dad, John Marshall, who had, as a boy himself, watched the men in the woods snake out those trees and pull the wagons with not only mules, but oxen. John Raymond had picked up a piece of history. An iron Oxen shoe. But like so many of us when we are young, he kept it for a while then lost it. At that point in his life it meant very lit

Many years later, as a ninety-year old man talking about it, he would have been proud to have it nailed above the door of his little workshop. It would have made a fine conversation piece. It would have also been one of the very few items to help bridge the gap, another something that his father had held in his hands.

Switching over to boards that weighed less than twenty-five pounds must have been a no-brainer. Admittedly the boards in a house lasted longer than railroad cross ties, but there was a never-ending construction of houses as Middle Tennessee’s population grew by leaps and bounds. Not many new railroad lines were added to the ones already existing. For Leander and Jim, the decision would have been an easy one.

A receipt remains proof of that. In 1904, when Leander was 64 years old and Jim was 42, Jim signed a bill of purchase for a sawmill, the largest available, for $1,000. Five hundred dollars down, the rest to be paid after the sawmill was operable. This transaction was completed when the average worker in America made about twenty cents an hour. Making cross ties though finally became a big money maker for big operations.

By the time Jim’s grandson, James Robert, was born in 1927 a fellow named Hobbs in Bentonville, Arkansas became the crosstie king of America turning out millions of them in big sawmills. When James Robert was married in 1950, there was another event in Bentonville; man named Sam Walton opened a five and dime store. Making crossties there took a back seat to what grew out of this small store; Walmart.

At that time in our country’s educational progress a sawmill operator needed as much college education as a Medical Doctor. Doctor’s did not have to attend college at all, just a medical school that pursued basic medical issues. Of course, sawmill operators probably didn’t get even a grade school education. Doctors then had a yearly salary of about two thousand dollars; about what today’s doctors make in less than a day, some make that much in five minutes.

While Jim was signing the bill of sale for that big sawmill, there was a baby girl still in diapers, hundreds of miles away in Kansas who one day would bring three of Jim’s grandsons into the world. A fourth was born to his daughter just four years after he bought the sawmill. But that boy, as a twelve-year-old, met an untimely accidental death.

This little baby girl had an interesting journey though before she delivered those three grandsons. Jim would die just four years after his third grandson was born. They had named that grandson, Jim.

The sawmill was moved to a location on Little Marrowbone. Probably at a location at the mouth of Archie Hollow…about three miles down the Little Marrowbone from the Setters Home. The sawmill was to be delivered by November 1904, and from all indications, it was. Nine out of ten sawmills at that time were powered by steam engines. Of course, they burned wood to boil the water to get the steam. There was an endless supply of fuel.

Jim’s son, John, was twelve years old. When Jim paid that five hundred dollars down on the sawmill, there was a little eleven-month old baby girl about six hundred miles away in the flatlands of Kansas. Neither the twelve-year old boy nor his 42-year old father would have been very interested if you brought it up. But this little girl was to play an important role in their lives.

In thirteen years, John would join the Army, go to the horrible trenches of France during World War One. The year he joined the Army that little girl was promoted from the fifth to the sixth grade with a grade average of A as a student in the Melbourne, Florida High school. The next year John was discharged from the Army and that little girl’s mother died. John would meet that girl in three years when she was eighteen years old. He would be twenty-eight. Both of their lives were about to change dramatically.

Life can be very strange and sometimes very cruel. If you had told this baby girl’s mother, Gertrude Roberts, that in fourteen years she would die in Florida after having added seven more children to the family, and had you told John’s mother Carrie, that her grandson would be hanged from a tree in her front yard a year after Gertrude died, both would think you were out of your mind.

Be assured Leander was not all about Leander. He cared for others and particularly those down on Little Marrowbone. He contributed to the road building and donated all of the material for the Church of Christ building and a small school and paid the salary of the teacher. For several years his cross tie and lumber mill were the only entities that employed men in the six-mile long valley.

Many of the roads bear men’s names around Nashville, but most are named for the town they serve. For example, if you leave Nashville heading to Clarksville it is the Clarksville Highway. At one time the Clarksville Pike. When you leave Clarksville, going to Nashville, the same road is the Nashville highway. In the late eighteen hundred’s, the roads were not built by the government, they were built by individuals or companies. And tolls were charged. They were called Pikes.

Little Marrowbone was always known, as far as Leander was concerned, as Little Marrowbone. There is now a Setters Lane in Nashville, but it was named that because of Leander’s son Bill and daughter-in-law Sallie, not because of Leander.

America was getting deeply involved in the industrial industry of the time. The sawmill arrived just three months after Henry Ford incorporated the Ford Motor Company. The famous Model-T Ford, the tin lizzy, was introduced four years later.

And about 700 miles away, one month before the sawmill arrived, in September 1903, there was another delivery. A baby girl. They named her Esther. In about eighteen years she would become Jim’s daughter-in-law. Esther’s last son, Jim’s grandson, would be born in 1927, the year they stopped making the Model-T Ford. Then they began making the Model-A. As the Ford automobiles got better, the economy got worse; along came the great depression.

But, a lot happened during those eighteen years. Jim’s son, John at about twenty-five years of age would marry, give Jim his second grandchild, a girl. Then about four years later John would marry again. To Esther; from that marriage Jim would gain three grandsons.

His daughter Bertha was married, had a son. Let us digress a bit. Now that Bertha has entered the picture be prepared to later on in our story follow a few years of her life, at least some of the good and some of the not so good.

She played an important role in The Lake. You might say that because of her, the lake is the way it is today……. beautiful. But it didn’t happen just accidentally. A lot of folks had played a part.

Exactly when Leander’s son Jim became part of the Setters operation on Little Marrowbone is not really known, it is believed to be about 1905. Did he travel down by himself? Did he bring John with him? Unfortunately, there is little known about that. We can assume many things, but it would just that, an assumption. We do know that Jim bought the sawmill in 1904 and had it delivered to Little Marrowbone.

There were more sawmills in the Little Marrowbone community than there were telephones. That was true up until the middle of the nineteen forties simply because the telephone service did not show up in that hollow until then. Nor did electricity. Water service came in the early nineteen eighties.

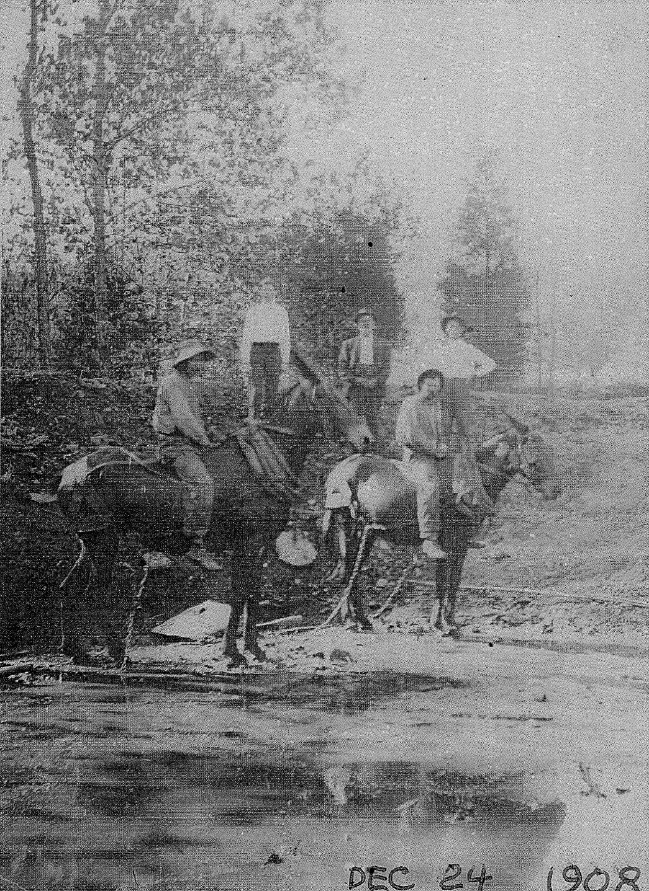

All of this leads up to December 24, 1908. Someone, with one of those big bulky crude cameras, snapped a picture of Leander and his boys, not his sons, a couple on mules, as they dredged out a pond. Why a pond? Well, for one thing, Leander had some cattle – as was evidenced in his will in 1917. The previous winter the folks on Little Marrowbone received only a trace of snow, and that is still a record.

When Leander and Louisa arrived on Little Marrowbone, in 1888, the peach trees bloomed in February. In the picture taken on that Christmas eve, late on a Thursday afternoon, 1908, twenty years later, Leander stands proudly between the two young men in light covered shirts behind the pair of mules. Leander is facing Southeast. The shadows on the ground tell us it was late in the afternoon. It was time to stop working.

1908, the year Leander became a great-grandfather. His grand-daughter Bertha had a son. He was named James Lloyd Rice. Leander, who by now was 68 years old, still had an eager and active mind. Since the water in the Marrowbone creek was pure and drinkable, (and for some still is although for a while E.coli was an issue) and since the first very crude ice making machines (the first patented in 1855 and then not even pursued commercially) and as has or will be noted in our story the family that originally built the lake before 1871 used the lake for making ice, so did Leander. So, he had his men scoop out the muck. Years later, and still is, known simply as Setters Lake.

It is the only feature on Little Marrowbone that is on official maps of the State of Tennessee. And he did that at the age of 68. And strangely enough, he was a lumberman, not a hydrologist.

Twenty days before the picture above was taken, a baby named Lester Joseph Gillis, was born in Chicago. As an adult, Lester was a small man with a youthful appearance. He had a strange career ahead of him. He was later known as Baby Face Nelson, the famous murderer and bank robber. His wife and family called him “Les”.

Two dozen years later and a two hundred-mile drive west of Chicago, there was another birth, in Iowa; a little girl baby, she would one day play an important role in Setters Lake. A man named “Les” played a part in her life. Maybe not as bad as “Les” also known as, Baby Face Nelson. But bad, just the same. We’ll tell you all about her later. Baby Face was killed when seventeen bullets tore into his body by police gunfire when that baby girl was three years old. In fact, she is one of the two ladies in the picture on this page.

If you were to ask the young man on the left of the picture of Leander and his boys scooping out the lake, the one sitting on the big blackest mule, if two good looking women would be standing on the ice at about his head level in three-quarters of a century, he probably would just look at you. First of all, he more than likely had no idea what you meant by three quarters of a century. Further- more, there is no way he could have visualized ice being that thick just a few inches over the top of his hat. The further complicate things, in 1908 very few women wore trousers. He would have been mystified to learn that these two women were sisters who were raised in the flatlands of Kansas, more than five hundred miles away. The one on the left, Dana, was Leander’s great-granddaughter-in-law, married to James Setters, the grandson of Leander’s own son, James. By the time you got all of that explained, the young man and the mule would probably have gone to the barn and called it a day.

As the men hired by Leander were moving the mud out of the lake, earth was being moved more than five thousand miles away in Messina, Italy.

An earthquake. It caused a huge wave, a tsunami, that killed more than seventy thousand people less than a week after the picture was taken of Leander and the men and mules and scoops. We doubt the guys sitting on the mules ever heard about it, nor did Leander. The tragedy in Messina might have been brought up in conversations with some of the families of immigrants from Italy, maybe the Ida or Conchin families, but an event in the Mediterranean Sea was not something that was talked about on Little Marrowbone.

Of more interest to Leander though was another birth, his first great-grandson, Lloyd. His mother Bertha, his grand-daughter still lived up in Kentucky. He left his son Jim, Jim’s wife and Bertha there twenty years earlier when Bertha was just a year old for another life in Tennessee.

Actually, there is no record that Leander ever called the little body of water a lake. In his will, drafted seven years after he built the lake, he called it a pond. So officially it really should be called Setters pond, not lake. There also was a barn on the five-acre sitting separately from the hundreds of other acres he owned.

One just doesn’t dam up a creek to build a lake. When the heavy rains come, and the creek becomes a roaring muddy mess tearing down trees and scooping out everything in its path your dam is either washed away or it is filled in with gravel and mud.

Leander had lived on the banks of that creek now for twenty years. He knew its nature. How it could become ugly. He also knew its beauty and purity. He knew he could become its friend. It’s quite possible that he was inspired by the United States taking over the construction of the Panama Canal just five years earlier. A kind of if they can do it, so can I.

Twelve miles from his home on Little Marrowbone stood the Davidson County courthouse, right in the center of nearly one hundred fifty thousand people who needed ice. Leander was building a little lake, about two acres total, that in the winter could freeze ice a foot and a half thick.

But when the water was being frozen, so was everything else. Who wanted ice in the winter? Leander knew the Winters family sold ice from the lake. About six feet down on that property was solid rock. He knew that solid rock was just eight feet deep. So, making ice was no problem. It was made with the water in the lake that of course was fed by the Little Marrowbone Creek.

You might think, wow, can you imagine people chipping ice off a big block of that ice that came from the lake and dropping the pieces of ice into their tea! But keep in mind if you will, it wasn’t until Leander built the lake in 1908 that the first city in the United States, Jersey City, New Jersey began to routinely disinfect its public water for homes and restaurants. Other cities quickly followed but up until 1908 no municipal water supply was treated for anything but appearance.

He had his men saw down a huge oak tree, used mules to position it across the creek at the “upper end” of his property, they used thick boards to form the dam. A ditch was dug for the water to run into their big excavation….and presto! A lake of pure drinkable water. When the creek roared with muddy water, simply close the ditch to maintain the water’s purity.

Oh! The ice? The Winters family had big pits made in the small meadow around the lake and when the lake froze, saws much like they used to work with the trees (except being worked from one end only), sawed the ice into big chunks. This was done years before Leander bought the property. In fact, a small house beside the road was mentioned as early as 1871, 37 years earlier. The chunks of ice were put into the pits, surrounded with very thick layers of straw and when summer came, Leander sold the ice. Very basic and by today’s standards crude? Yes. Effective? Yes.

Years later the lake served as a catalyst for another kind of thirst.