By the time Esther had her first baby, in 1923, Frigidaire introduced the first self-contained unit. The Roberts probably didn’t participate in the new gadget. In fact, Esther would not enjoy the many advantages of the home refrigerator for nearly a third of a century after it was first introduced. She was destined to live hundreds of miles away from her family in Florida. She would spend the first eighteen years as a mother, where there was no electricity. If she wanted to keep something cool, she kept it in a big box like container with a piece of ice. It was called an Ice Box. Her oldest son would be nineteen years old before she lived where there was electricity available.

By the time Esther had her first baby, in 1923, Frigidaire introduced the first self-contained unit. The Roberts probably didn’t participate in the new gadget. In fact, Esther would not enjoy the many advantages of the home refrigerator for nearly a third of a century after it was first introduced. She was destined to live hundreds of miles away from her family in Florida. She would spend the first eighteen years as a mother, where there was no electricity. If she wanted to keep something cool, she kept it in a big box like container with a piece of ice. It was called an Ice Box. Her oldest son would be nineteen years old before she lived where there was electricity available.

Esther’s mother, Gertrude Roberts, died August 10th,1918; exactly five years before the 50th wedding anniversary of Daniel and Elizabeth, her father and mother-in-law. Gertrude left nine children, including her youngest. Esther was just two months from her fifteenth birthday. The 1920 Melbourne census shows the children ages, in descending order, 17,16,14,13,11,9,8,6,3 and 1. The two-year gaps must have been when three newly born babies didn’t make it.

Twenty-one years later Wayne, the three-year old in the census, a small somewhat mentally challenged man was drafted into the Army during World Two. During a fire fight near the Battle of the Bulge, Wayne’s squad was forced to seek safety in a farmhouse from attacking German soldiers. The entire squad was captured.

Wayne spent several months as a prisoner of war in Germany. Wayne was just one of many thousands of American soldiers who tromped across the fields of Europe but just Wayne and a few others were able to say they walked as German soldier sentries. He was with a group of POWS doing work at a r  ail yard in a German city and being guarded by one of the local elder soldiers, Sgt. Hans Shultz, who were put into duty in the last months of the war.

ail yard in a German city and being guarded by one of the local elder soldiers, Sgt. Hans Shultz, who were put into duty in the last months of the war.

All in his POW group were young, says Wayne, and the guard was old enough to be their father. It was bitterly cold and windy in the railyard and they used a big steel drum rigged up as a stove in one of the boxcars to keep them warm.

The German guard never left the warmth though, he would give his topcoat, helmet and rifle to one of the American soldier prisoners and have them pose as him outside while the other prisoners would be working. The rifle was not loaded. Wayne said, “We had no place to go, had no idea where we were, and would probably have frozen to death had we tried to escape.” The old guard, Sgt. Schulz, stayed warm and cozy. One of Hitler’s storm troopers he was not.

What Wayne did not know was that one of his nephews, Harold Setters, named after Wayne’s brother, was one of the crew members of B-24 bombers that made raids on railroad yards just like the one where Wayne was. And the soldiers could have been cleaning up from such a raid. Lucky for Wayne, they never raided that one while he was there. Esther, fortunately, was totally unaware of what was going at that railroad yard. And that was good. Nor did Chancellor Adolph Hitler, General George Patton and Sergeant Setters. And that was good. This very well could have been the B-24 bomber in which Harold is seen in the bottom turret watching the bombs fall. He had no idea of course that his uncle Wayne was probably down there, thousands of feet below, trying to dodge the bombs. The ball turret gunner, or belly gunner as it was known, is looking straight down as the bombs fall.

What Wayne did not know was that one of his nephews, Harold Setters, named after Wayne’s brother, was one of the crew members of B-24 bombers that made raids on railroad yards just like the one where Wayne was. And the soldiers could have been cleaning up from such a raid. Lucky for Wayne, they never raided that one while he was there. Esther, fortunately, was totally unaware of what was going at that railroad yard. And that was good. Nor did Chancellor Adolph Hitler, General George Patton and Sergeant Setters. And that was good. This very well could have been the B-24 bomber in which Harold is seen in the bottom turret watching the bombs fall. He had no idea of course that his uncle Wayne was probably down there, thousands of feet below, trying to dodge the bombs. The ball turret gunner, or belly gunner as it was known, is looking straight down as the bombs fall.

When Wayne was on Army maneuvers in Middle Tennessee, he visited Esther and his nephews. It was only the second time she had seen him since she left him as a four-year old in Florida. A black and white photo shows him sitting between his two nephews in the house Esther had rented on 8th avenue south in Nashville. The last house Raymond and Harold lived in before they entered the military.

Raymond who was also in High School when Wayne visited, was draft age, enlisted in the Navy and was part of the invasion fleet that deposited soldiers like Wayne at Normandy on the now famous D-Day on Omaha Beach. He was a crew member on one of the landing ships for tanks. Later, after he returned home and married, he finally earned his GED, a high school diploma. Raymond, contrary to his earlier years, as not a very accomplished student, made the highest grades in his

Civilian GED class. He was no longer under the negative influence of his father. But you could never in a thousand years convince Raymond that was true.

While serving with the Navy on Normandy,  his main job was to keep the big gasoline engine running but was also called on to operate the guns on the big clumsy craft. In addition, he was called on to go ashore and try to demolish the barricades the Germans had installed under the water on the beaches. Esther’s oldest, Harold, was already in the Army Air Corps, in 1947 renamed U.S. Air Force.

his main job was to keep the big gasoline engine running but was also called on to operate the guns on the big clumsy craft. In addition, he was called on to go ashore and try to demolish the barricades the Germans had installed under the water on the beaches. Esther’s oldest, Harold, was already in the Army Air Corps, in 1947 renamed U.S. Air Force.

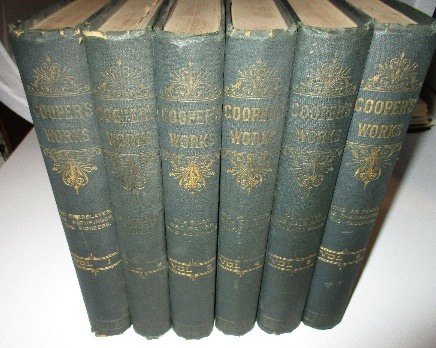

But let’s turn back the clock for about twenty-four years, back to Melbourne. One day, in 1921, as she sat on their front porch, Esther watched with interest as a man walked toward her. He had gray eyes and a friendly smile. At least, this is how she described their first meeting in a short one paragraph biography written on the inside cover of a Cooper’s Works book.

But let’s turn back the clock for about twenty-four years, back to Melbourne. One day, in 1921, as she sat on their front porch, Esther watched with interest as a man walked toward her. He had gray eyes and a friendly smile. At least, this is how she described their first meeting in a short one paragraph biography written on the inside cover of a Cooper’s Works book.

The set of books which one of her sons, Jim, remembers included the famous story ‘Last of The Mohicans‘, was on a little shelf in their small house on Little Marrowbone for years. Where it is now, is a mystery. One thing for sure, it is worth in today’s dollars a good sum. And the brief description of this encounter probably means little if anything to the present owner of that set of books. When Esther’s youngest son read that paragraph, in the middle nineteen thirties, you would have had trouble trying to give that book away.

Back to Esther sitting on her front porch in Melbourne, Florida. This man she was watching was John Setters. Esther was eighteen years old. John was twenty-nine. He had already fathered a daughter, had been to war and was gazing at a teen-aged girl. She was gazing back.

Do you see how important just a few details can be? Were you not there watching these two people, this man and the girl, as their lives were being changed? To have lived those few seconds with them, knowing how this chance meeting set the wheels in motion that affected Leander’s lake, hundreds of miles away? Now we know the why of so many years that followed and are still unfurling. The question of “how in the world did these two ever get together” was answered. But the why?

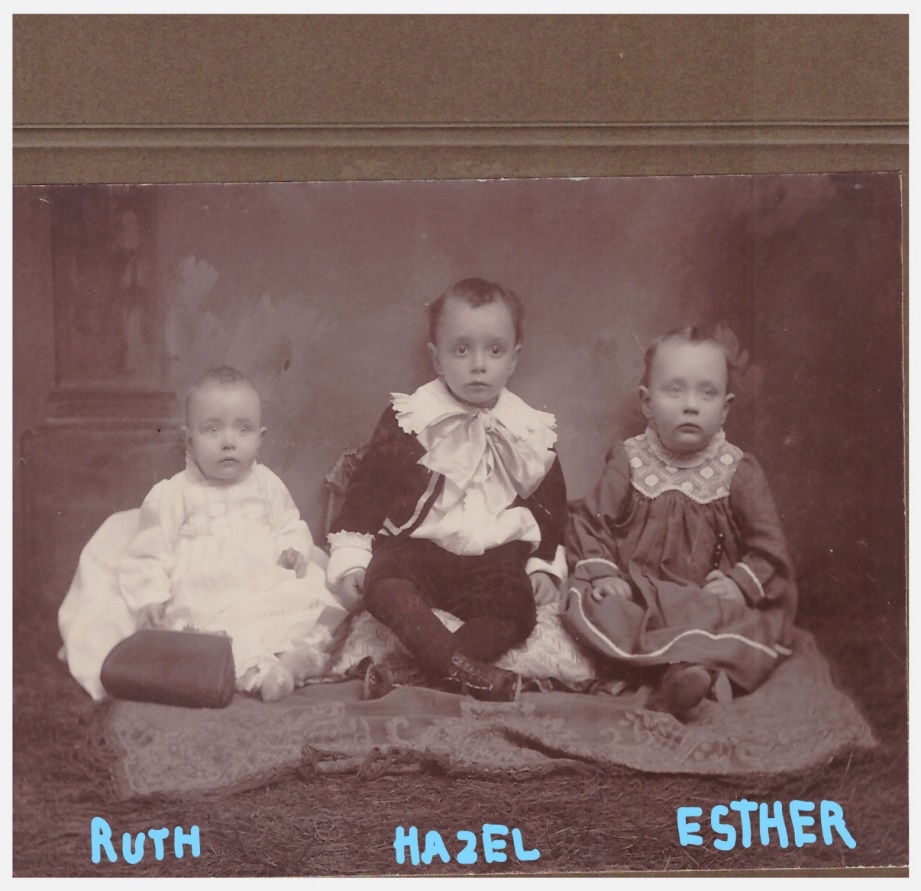

There were three sisters in that Roberts household, with the fourth only recently born of a woman who gave birth to nine children. In the front is Ruth, who will play an important role in Esther’s life. Not for her presence, but because of her absence. Ruth, strangely enough, is listed as having been born in North Carolina, just two years after the birth of Esther, who was born in Sumner County Kansas. No explanation is given as to why their pregnant mother, Gertrude, was in North Carolina, over a thousand miles from Clearwater, Kansas. In the middle is Hazel, who had three daughters and who will remain in Melbourne the rest of her life. Esther, who had told her daughter-in-law that every mother should have a daughter, but she had three sons. In back is Esther, obviously the prettiest of the three. In the middle is Hazel, then Ruth. Ruth’s death will play an important role in Easter’s life years later. John chose Esther. Or was it the other way around. We’ll never know, will we? Notice their faces, gentle smiles on all three. Contrary to the expressions that we have seen on most of the ladies in our earlier story.

There were three sisters in that Roberts household, with the fourth only recently born of a woman who gave birth to nine children. In the front is Ruth, who will play an important role in Esther’s life. Not for her presence, but because of her absence. Ruth, strangely enough, is listed as having been born in North Carolina, just two years after the birth of Esther, who was born in Sumner County Kansas. No explanation is given as to why their pregnant mother, Gertrude, was in North Carolina, over a thousand miles from Clearwater, Kansas. In the middle is Hazel, who had three daughters and who will remain in Melbourne the rest of her life. Esther, who had told her daughter-in-law that every mother should have a daughter, but she had three sons. In back is Esther, obviously the prettiest of the three. In the middle is Hazel, then Ruth. Ruth’s death will play an important role in Easter’s life years later. John chose Esther. Or was it the other way around. We’ll never know, will we? Notice their faces, gentle smiles on all three. Contrary to the expressions that we have seen on most of the ladies in our earlier story.

Esther as a late teen, about the time she was sitting on that porch. She is holding an orange in her right hand, and she was sitting in the family orange grove under an orange tree. She was about eighteen years old. Her dad brought the family to Florida from Kansas in 1912, when Esther was just nine years old. And since it takes about four years for a newly planted orange tree to produce fruit, and since Lawrence had a wife, between pregnancies, and several healthy children to work, it is easy to see that nine years after the family began working in the orange groves, and they all did, Esther told her granddaughter, she could easily be sitting under one of the trees holding an orange even before she reached the age of eighteen,

The picture below was taken of the children when they were just tiny little girls, still living in Kansas. They had not yet developed those beautiful smiles.

Ever wonder how you would react if someone just walked up to you and told you what is going to happen to you in the years ahead. If Lawrence and Gertrude Black had been told that Ruth and Esther would someday marry the same man and that Hazel would marry a man in Florida that sold frogs to New Yorkers and that her first husband would be killed by a pistol in their bedroom by an intruder who never was identified.

Ever wonder how you would react if someone just walked up to you and told you what is going to happen to you in the years ahead. If Lawrence and Gertrude Black had been told that Ruth and Esther would someday marry the same man and that Hazel would marry a man in Florida that sold frogs to New Yorkers and that her first husband would be killed by a pistol in their bedroom by an intruder who never was identified.

Harold, the first born, with a frilly shirt but with long pants is in the center.

Hazel Harold Esther

Do you think Lawrence and Gertrude would do anything but laugh? And to further complicate the issue, Esther would marry a man who had fought Germany in a war, and she, would give birth to sons who would also fight Germany in another war. Tell me, does that little girl on the right, Esther, look as though she is destined for all of that? Time will tell. Things happen, don’t they? And things change.

Lawrence Roberts was father to nine. In the picture above are the first three of them. Esther was the first to marry and leave home. Hazel was the second, but her first husband was murdered in their bedroom in Melbourne. Like her older sister Esther, Hazel next married a World War One veteran. When she died at age 82, in 1988, no mention was made of her earlier marriage of course. There was no need. Like Esther, Hazel had lived a very productive life. And like Esther, Hazel was the mother of three children. Esther had three boys, Hazel, had three girls. Their sister Ruth, who married her boss in Wichita, Kansas, in 1935, had no children.

Lawrence Roberts was father to nine. In the picture above are the first three of them. Esther was the first to marry and leave home. Hazel was the second, but her first husband was murdered in their bedroom in Melbourne. Like her older sister Esther, Hazel next married a World War One veteran. When she died at age 82, in 1988, no mention was made of her earlier marriage of course. There was no need. Like Esther, Hazel had lived a very productive life. And like Esther, Hazel was the mother of three children. Esther had three boys, Hazel, had three girls. Their sister Ruth, who married her boss in Wichita, Kansas, in 1935, had no children.

First husband Hazel

We know how Esther got to that front porch, but we must get John to Melbourne, Florida. John and his sister, Bertha were born in Kentucky. Bertha in 1888 and four years later, John, July 5th, 1892. Bertha’s involvement in Leander’s lake, yes, her grandfather’s lake was an important one. But let’s go into more detail about that later. More often than not, events direct our lives. Events over which we have no control and in which we have little if any input.

And these events can take place on days of our lives that are supposed to be happy and meaningful. This was the case with John, and twenty-seven years later, his son Harold, on their birthdays. For John, an event thousands of miles from him on July 5,1914, on his 22nd birthday. Germany assured Austria that she could count on Germany’s “faithful support” if whatever punitive action she took against Serbia brought her into conflict with Russia. This was the signal that let loose the irresistible onrush of historical events… and the beginning of World War One. And we bring John Marshall Setters into our story.

For Harold, John’s son, on his 18th birthday on December 7th, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor; the beginning of World War Two. The Setters family still lived on little Marrowbone when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, but Harold was living with Bertha in Nashville and attending Hume Fogg High School. His brothers, Jim and Raymond, learned about the attack from Jay Sellick, a friend who had heard it on his car radio. The Setters home still had no electricity. Harold, in later years as a gunner on B-24 bombers, never flew a mission against the Japanese, but he flew thirty-five against the Adolph Hitler crowd, then later, on a B-29 over Korea.

John joined the Army at age 25, in 1917. His 25th birthday fell just two months after Rose and Joseph in Massachusetts welcomed their second son into the world. He was also named John. John Fitzgerald Kennedy. John Kennedy died five months before his 47th birthday. John Setters died in 1947, three months after his 55th. They died from very different causes and lived in two very different worlds. Both Johns served in great wars; John Setters in World War One, the war that was meant to end all wars. John Kennedy served in World War Two. Obviously, World War One failed to end anything. About the same can be said of World War II. John Kennedy was a war hero, came home and became President of the United States. John Setters simply came home. John Kennedy was able to leave his PT-Boat with a badly injured back. John Setters was never able to leave the trenches. His injuries were emotional. We have a name for John Setters war injuries. We now call it Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

A year before he joined the Army, in 1917, 24 years-old John Setters married a Nashville girl; 17-year-old Ruby Carney, on October 21st, 1916. Four months before they were married, in a cabin at the corner of First and Oldham streets, the story goes, a young boy’s ball, simple ravelings, of an old yarn sock, landed in a red-hot stove. The boy, in what The Nashville Tennessean later pronounced as “a desperate effort to save his toy,” snatched it from the grate and threw it out the door. in the yard where it landed, the grass, dry and overgrown, ignited. Wind gusts whipped the flames.

A year before he joined the Army, in 1917, 24 years-old John Setters married a Nashville girl; 17-year-old Ruby Carney, on October 21st, 1916. Four months before they were married, in a cabin at the corner of First and Oldham streets, the story goes, a young boy’s ball, simple ravelings, of an old yarn sock, landed in a red-hot stove. The boy, in what The Nashville Tennessean later pronounced as “a desperate effort to save his toy,” snatched it from the grate and threw it out the door. in the yard where it landed, the grass, dry and overgrown, ignited. Wind gusts whipped the flames.

And in less than five hours on a blustery day, disaster blackened the east bank of the Cumberland River and forever changed the composition and identity of the city. Thousands were made homeless, and that part of Nashville was forever changed. A thirty-five-block area was left looking like this picture. The, then affluent neighborhood, never fully recovered and is now the site of Nissan stadium where the Tennessee Titans play football. In another marriage and the year his third son was born, a violent tornado further pounded the same neighborhood.

But John was not affected by that fire or the tornado. He became one of hundreds of thousands that answered the call to go to the trenches of France to fight the Germans. At the age of twenty-five he enlisted in the Army. His mother, Carrie, then living in Nashville, instead of out in the hills on Little Marrowbone, may or may not have heard the song being sung in protest of the United States getting involved in the war in Europe, “I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier. In, two years, Carrie would suffer an almost unimageable tragedy in her own front yard, while she was in her kitchen cooking supper, it was then called.

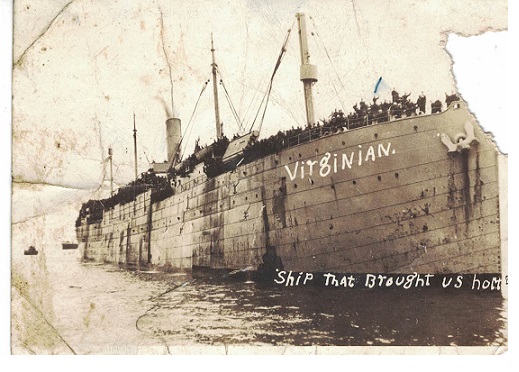

This picture of the troop transport the Virginian was found in John’s belongings by Vickey Setters, one of John’s daughters-in-laws. He had written on it, “The ship that brought us home.” From its appearance it barely made it back, but you can see the soldiers anxiously standing on the deck.

This picture of the troop transport the Virginian was found in John’s belongings by Vickey Setters, one of John’s daughters-in-laws. He had written on it, “The ship that brought us home.” From its appearance it barely made it back, but you can see the soldiers anxiously standing on the deck.

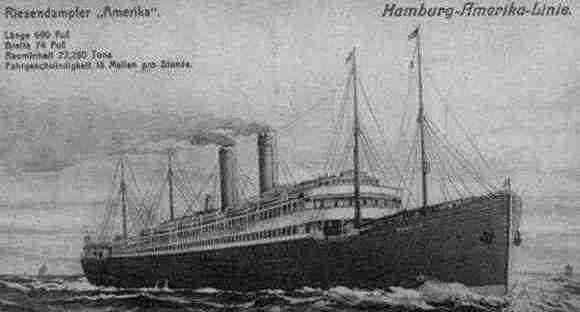

Vickie’s Dad, Emanuel Ponter, an immigrant from Croatia, came over on the Amerika-Linie, in 1910, eight years before John’s trip home. The ships are certainly different in appearance, but the emotions of both men were about the same. Emanuel was happy to be leaving Europe and so was John. John was thankful to survive the war and Emanuel was glad to leave Europe before the war started. For Vickey’s dad it was a one-way trip and he was leaving his home. For John, it was the completion of a round trip, and he was going home.

Vickie’s Dad, Emanuel Ponter, an immigrant from Croatia, came over on the Amerika-Linie, in 1910, eight years before John’s trip home. The ships are certainly different in appearance, but the emotions of both men were about the same. Emanuel was happy to be leaving Europe and so was John. John was thankful to survive the war and Emanuel was glad to leave Europe before the war started. For Vickey’s dad it was a one-way trip and he was leaving his home. For John, it was the completion of a round trip, and he was going home.

He had survived the danger of the first part because German submarines were very active. In the course of events, German U-boats sank almost 5,000 allied ships. Germany lost 178 U-boats and about 5,000 men. Emanuel never dreamed of course that he would father three sons who would, in about twenty years, go back to Europe to fight against the Germans. And John never dreamed he would father three sons who would be a part of that same war.