The Battle of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, signaled the start of the Civil War, the bloodiest conflict in American history, ending with at least, 620,000 dead Americans.

The Battle of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, signaled the start of the Civil War, the bloodiest conflict in American history, ending with at least, 620,000 dead Americans.

On April 12, 1861, forces from the Confederate States of America attacked the United States military garrison at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. By 1860, the final census taken before the American Civil War, there were four million slaves in the South, compared with less than half a million free African American citizens.

Now, what about David Rhodes, who was he?

David was born March l8th, 1841, in Cass County Indiana, eleven months after Leander Setters was born and about 275 miles northwest Leander’s birthplace in Olive Hill, Kentucky. David’s father was Thomas Jefferson Rhodes. One would assume that he was named after our third President Thomas Jefferson, who died fifteen years before David was born.

Neither Thomas nor Leander had a clue of course, as they lived their separate lives, that in one hundred and nine years after Leander was born that two of their great-grandchildren would marry one another or that this country would have fought a Civil War in which over half a million would die. The Civil war was fought over the rights to have slaves, By the time the first shot was fired, in 1861, there were

When David was twenty years old, the civil war had just begun. Leander was twenty-one but married and with a small daughter, one on the way and a son that had died shortly after birth. David joined the Union Army.

He had blue eyes, fair complexion and was described as being tall. Not by today’s standards though. He stood only five feet six inches.

The same height as Leander’s grandson, John Setters, when he joined the army in 1917, fifty-six years later. David was an infantry private, in the Union Army’s 29th regiment.

In 1863 his regiment fought at Chickamauga, Georgia where he was wounded and captured by the Rebel Army. Among the thousands of Confederate soldiers that David fought was Private Thomas Benton Johnson from Somerville, Alabama, who was also wounded in that war. We mention this because Thomas was the great-uncle of a little Alabama girl named Vista Ponter, who married one of Leander’s great-grandsons, John Raymond Setters, nearly a hundred years after the Civil War began. As far as we know, David and Thomas never met in that battle. As far as we know. We do know that David suffered what we now understand, as Post Traumatic Syndrome. Thomas, who fought in many battles, probably did too. But not much was made of this in those times.

But both, shed blood in battle, during that terrible war.

This complicated, military and politically important battle took place near Chattanooga Tennessee and has been described as just under the battle at Gettysburg in importance to the Union. Although not really won by the Union, the Union army prevailed well enough to give Abraham Lincoln a victory in his re-election the following year. If you have ever been in Chattanooga and have even a slight understanding of the terrain, you can realize what a tough time those in command of what surely was a badly trained infantry had.

The man who was opposing Lincoln had pledged to stop the Civil War and then leave the South to its own system. He surely would have defeated, an already weakened, Lincoln.

Our Nation would have ceased to exist as we know it today. Did David fire the shot that made a positive outcome possible? Doubtful. But he WAS there, and he DID fight, and he was wounded.

David was rounded up along with several thousands of Union soldiers and spent months at the infamous and horrible prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia. Andersonville, or Camp Sumter as it was officially known, was one of the largest of many established prison camps during the American Civil War. It was built early in 1864 after Confederate officials decided to move the large number of Federal prisoners kept in and around Richmond, Virginia, to a place of greater security and a more abundant food supply.

During the 14 months the prison existed, more than 45,000 Union Solders were confined here. Of these, almost 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, or exposure to the elements. If the move was made for a better food supply, it was a total failure. In spite of the dislike of the Yankees, many of the Georgia area folks would bring food and other supplies to help the prisoners. The prison camp commander made every effort to prevent these acts of mercy. Starvation and disease were rampant. One soldier wrote, “It takes seven of us to make a shadow.” Nearly a thousand died every month. By the way, descendants of David Rhodes can visit the camp memorial. It is south of Atlanta.

Those who have visited say. “You won’t be the same after your visit”.

Every day they would pile up the dead, on wagons and haul them outside the camp for burial. David was found emaciated, limp and unconscious, he was loaded onto a wagon, as dead, but someone saw his toe move. He was taken to a hospital in Charleston, SC. At least he was spared the biggest U. S. Navy ship tragedy of all time, until Pearl Harbor.

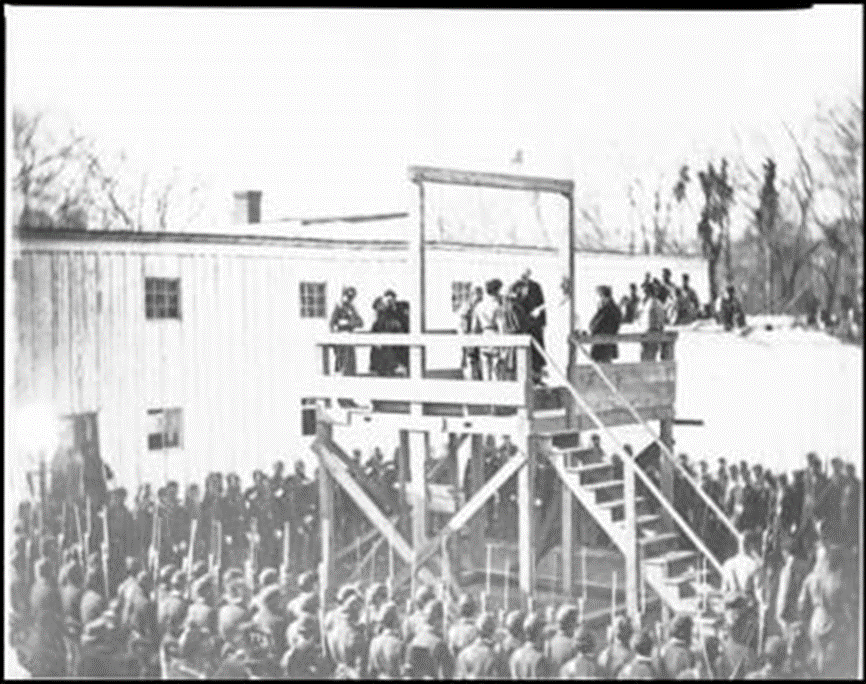

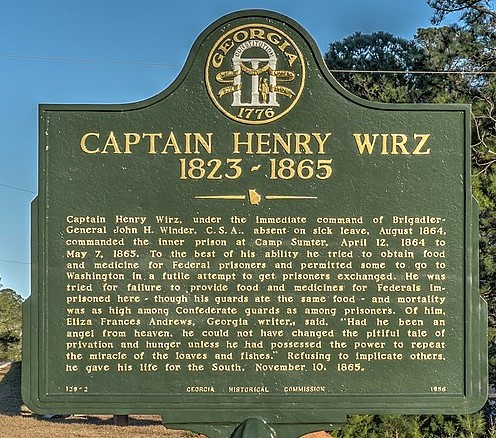

Confederate Army Captain Henry Wirz was the camp commander. He was hanged for his behavior at Andersonville, although even many of the prisoners felt the Confederacy gave such pitiful supply support to the camp, he really was helpless. But he was a cruel man. Born in Switzerland he fled from a war in that part of the world much like the one in which he became involved in this country. He had been here only twelve years before that shot at Fort Sumpter, S.C. Eleven days after he was hanged it was discovered that a star witness against him was a liar, fraud and a deserter from the Union Army. Captain Wirz’ neck did not break when he fell through the trap door, and he was watched by a crowd gathered for the event as he fought for breath and died by choking. The gallows were erected in Washington D.C. on a site that is now the location of the Supreme Court. It was November 10th, 1865, the 90th birthday of the U. S. Marine Corps. In just fifteen days Captain Wirz would have been 42 years old.

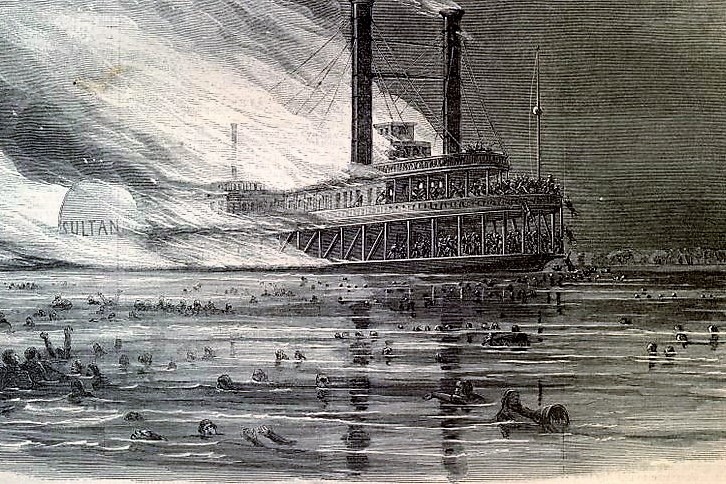

Thousands of the former Andersonville prisoners were transported by paddle-wheel boats from the south to the north. Eighteen hundred died when the Sultana sank in the Mississippi River in April of 1865, more deaths than were caused by the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, fifty-seven years later.

The event caused more Union Army deaths than were suffered at the battle of Chickamauga. The Army quartermaster officer, Rueben Hatch, who had pulled several shady deals before being put in charge of the quartermaster loading at Memphis, who criminally overloaded the Sultana was never prosecuted. The boat was designed to carry no more than 476. More than 2300 were crammed aboard. Hatch was paid a kick-back from the five dollars the government paid the operator of the boat for each soldier put aboard and twenty dollars for each officer. Hatch rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel and is a not too distant relative of Senator Orin Hatch of Montana. After Rueben’s death his wife moved to Montana where she was buried. Her grave marker also has Rueben’s name on it, but Rueben’s body was never moved from Illinois. An inscription on her gravestone reads, “Believe in the resurrection of the dead”, might well be a tribute to the eighteen hundred who died in that riverboat tragedy that was the legacy of Rueben, her husband.

There were documents showing that Abraham Lincoln himself intervened into his case that made it possible for Hatch to get the job to begin with. It was in April 1865, when the Sultana sank. The same month that Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Fate? Maybe. The trial of four men who were charged with involvement were hanged on July 7th. John Wilks Booth, the actor who shot Lincoln, was killed by a soldier. Booth’s mother had divorced his father, charging him with adultery.

Booth’s father and his mistress were married on John Booth’s 13th birthday. Thirteen years later, at the age of twenty-six, John shot Lincoln.

These events and dates are of importance in our story because of how they surely impacted the lives of Leander and Louisa. A year before the war began, Louisa gave birth to Sarah and John Marshall. John Marshall died a few months after he was born. During the war, James was born and William came just a year after the war was over. By this time Leander was the twenty-five-year-old father of three.

Put yourself there at that point in time; your country had just ended a horrible civil war, your President had been assassinated, a large part of your population that had been in slavery was freed, poverty was rampant, and no one knew what the future held.

And just one more thing, if you don’t mind. Although one or two states of the newly formed union made laws concerning the safety and wellbeing of people who had jobs, it was more than a century later, in 1970, that President Richard Nixon signed into law what we now know as OSHA, Occupational Safety and Health Act. This law brought thousands of rules and regulations to employees, especially factory workers. Had that law been in effect as early as 1840 history, as we know it, would have taken a different course. At least in one instance.

In a book published on July 4, 2009, Lisa Rogers reveals a strange set of causes and effects. She writes about a man named Thomas Corbett. You probably never heard of him. He was born in 1832, eight years before Leander Setters. Thomas had a job manufacturing men’s felt hats. Mercury was used in the manufacturing of felt hats during the 19th century, causing a high rate of mercury poisoning in those working in the hat industry. Mercury poisoning causes neurological damage, including slurred speech, memory loss, and tremors, which led to the phrase “mad as a hatter“. In the Victorian age, many workers in the textile industry, including hatters, often suffered from starvation and overwork, and were particularly prone to develop illnesses affecting the nervous system, such as tuberculosis. By the time Thomas Corbett was twenty-six years old his mind was badly affected, in fact he was probably insane. He picked up a pair of scissors, took off his pants and castrated himself. By this time, he had also become a religious fanatic. After cutting off his testicles, he put his pants back on, went to a Church prayer meeting, ate dinner and went for a walk. He did finally see a doctor.

Thomas Corbett enlisted in the Army at the outbreak of the Civil war, in fact, said Lisa in her book, he enlisted three times and reached the rank of sergeant. In 1865 he was assigned to a group of soldiers to hunt down a murderer. They cornered the suspect in a barn, but the suspect refused to surrender. The soldiers set fire to the barn and while the suspect was still inside Thomas watched him through a big crack in the wall. Thomas stuck his colt pistol through the crack and shot the suspect in the neck, killing him. Thomas later said, “God Almighty directed me.” He collected a reward of over sixteen hundred dollars. The man he killed was John Wilkes Booth, who only twelve days earlier had assassinated Abraham Lincoln.

The reason for all of this material about Thomas Corbett entering the story is this; it reflects the times and how things were in Leander and Louisa’s early life. Had OSHA, Occupational Safety & Health Act existed, chances are, Thomas would be normal and John Wilkes Booth would have stood trial and we would know better, why Abraham Lincoln was killed, at least as far as Booth is concerned.

Two years after he was wounded at Chickamauga, David was discharged from the Union Army on April 11, 1865, just three days before Abraham Lincoln was shot and about two weeks before the Sultana exploded and sank. The Sultana event was relegated to the back pages of the newspapers. After all, what was another seventeen hundred deaths in a war that had caused the deaths of over six hundred thousand.

My, my, were not the spring and summer of 1865 busy ones?

Later that same year, 1865, David married Sarah Esson. She was 26 years old, two years older than David. David took his new bride to the farm in Iowa, as a bonus from the Union for his service. Five of their six children were born there. One of these children was Jessie Rhodes, born in February 1873. Shortly after Jessie was born the family moved to Sumner County, Kansas just south of Wichita.

In 1910 Sarah and David moved to a farm near Frederick, Oklahoma.

Sarah died, four days before Christmas in 1912 at the age of seventy-three.

She had gone to Texas to visit some dear friends. Her body was returned by train and buried by a grieving David.

David was to live another 15 years. The demons of Andersonville never left him although his granddaughter, whom he visited after Sarah died remembers him with kind words. That granddaughter was Mabel, the mother of Dana. Mabel was the daughter of Bessie. The wife of Jessie, the son of David.

Sarah and David are buried at the cemetery in Frederick, Oklahoma.

Someone along the line, after his death, wrote these words about David; ‘The demons of Andersonville haunted him constantly. And another said, His final years were marked by second childhood.” Today we probably would refer to that as Alzheimer’s. The remnants of Andersonville, perhaps, if the disease needs a cause.

It was in Sumner County Kansas, that Jessie met and married a young redhead named Bessie Evelyn Smiley. Six years younger than Jessie, she was born September 19th, 1879, in Wellington, Kansas. They were married in 1898 when Bessie was nineteen years old. Bessie gave birth to five daughters and four sons. But where did Bessie come from and what do we know about her? Bessie’s father was J.W. Smiley. Her mother’s maiden name was Helen Dixon Esson, daughter of George and Sarah Esson. George and Sarah had moved to Kansas from Canada when Helen was nine years old. Helen was born in Peterborough, Canada June 7th, 1854. This was nine years before David Rhodes was wounded and taken prisoner at the battle of Chickamauga in the Civil war and sent to Andersonville Military Prison.

At the age of 21, just before Christmas in 1875 she married J. W. Smiley in Lawrence, Kansas. J.W. died just fifteen years later in 1890 but not before he had fathered two sons and two daughters. Several years before his death J.W. and Helen had moved their family to a farm near Perth, Kansas as homesteaders. Helen, known to the family then as “Grandma Smiley” lived for fifty-seven years on that farm as a widow.

All of her children moved on to live their lives except one son, Marion. Marion was mentally challenged but was a good worker on the farm. Some of Helen’s great grandchildren visited her a couple of times and were amazed at Marion’s memory. They would tell him their names and Marion would tell them the day and date they were born. Mrs. Smiley died one day from burns when their farm- house caught fire in 1947, Marion and his mother were putting wood into the stove and somehow the fire got started. (The year that the grandson of Leander Setters died of a heart attack, while waiting for a bus. Leander had died fifteen years earlier, in a “Poor House”)

All of her children moved on to live their lives except one son, Marion. Marion was mentally challenged but was a good worker on the farm. Some of Helen’s great grandchildren visited her a couple of times and were amazed at Marion’s memory. They would tell him their names and Marion would tell them the day and date they were born. Mrs. Smiley died one day from burns when their farm- house caught fire in 1947, Marion and his mother were putting wood into the stove and somehow the fire got started. (The year that the grandson of Leander Setters died of a heart attack, while waiting for a bus. Leander had died fifteen years earlier, in a “Poor House”)

“Grandma” Smiley had twenty-one great-grandchildren. The house fire brought her life to an end at ninety-two years of a life that saw many things that none of her off-springs will ever experience. This left poor Marion alone, so his sister, Pearl, let him move in with her family. Marion died in 1957, at the age of eighty, and was buried in Perth, just a few miles from the farm where he had spent his entire life, living under the watchful eyes of his mother, who, as things turned. out, was not watching as closely as she should. But making fires early in the morning and those Kansas Prairie winds, can be dangerous, no matter how many times you make ‘em.

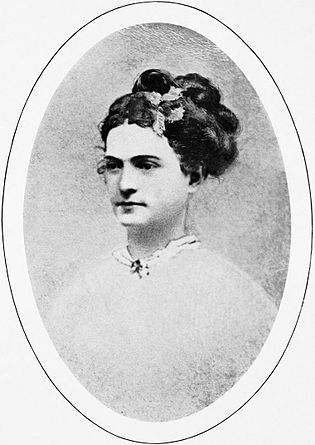

WE ALSO MUST INTRODUCE CLARA BARTON

SHE TOO, VISITED ANDERSONVILLE, BUT NOT LIKE DAVID

Portrait of Clara Barton by renowned Civil War photographer Matthew Brady, circa 1865.

“Let me go! Let me go!” On April 12, 1912, at nine o’clock in the morning, Clara Barton spoke those last words “and the earthly life of Clara Barton came to its close.” And so ended the life of the person who not only founded the American Red Cross but served as its First President and did so for its first twenty-two years.

According to the Red Cross website, when Clara Barton visited Europe in search of rest in 1869, she was introduced to a wider field of service through the Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland.

Subsequently, Barton, born Clarissa Harlowe Barton on Christmas Day (December 25th) 1821 in Massachusetts, read A Memory of Solferino, a book written by Henry Dunant, founder of the global Red Cross network. Dunant called for international agreements to protect the sick and wounded during wartime without respect to nationality and for the formation of national societies to give aid voluntarily on a neutral basis. The first treaty embodying Dunant’s idea was negotiated in Geneva in 1864 and ratified by 12 European nations. (This is called variously the Geneva Treaty, the Red Cross Treaty, and the Geneva Convention.) Later Barton would fight hard, and successfully for the ratification of this treaty by the United States.

When Jim and his buddy, a fellow Marine were hired by a Marine Colonel to mow the Colonel’s grass and ended up raising the ire of an Army Colonel, his neighbor, because the Army colonel’s teen-aged daughter seemed to be “intrigued” by the young Marines. Jim, at that time was totally unaware of David Rhodes, Joel Griffin, or Clara Barton. Betsy Ross, maybe, she made the first flag, and was one of the historical ladies brought up by the women teachers way back at Jim’s grade school, but not Clara Barton. Clara was a bit too complicated for boys, Jim’s age.

Jim still had nearly three to serve in the Marines before he was to meet Dana Chapman, whom he married on St. Patrick’s Day, in 1950, at her mother’s house in Wichita, Kansas. Kansas has a county that is named for Clarissa (Clara) Harlowe Barton. Great Bend is the county seat. Clara Barton helped to provide medical supplies to the Yankee soldiers during the Civil War and, of course, founded the American Red Cross in 1881, sixteen years later. The first courthouse was built in 1873. It is the only one of Kansas’ 105 counties to be named for a woman. Just look what your author did for those of you in Great Bend, that visit this website.

Jim still had nearly three to serve in the Marines before he was to meet Dana Chapman, whom he married on St. Patrick’s Day, in 1950, at her mother’s house in Wichita, Kansas. Kansas has a county that is named for Clarissa (Clara) Harlowe Barton. Great Bend is the county seat. Clara Barton helped to provide medical supplies to the Yankee soldiers during the Civil War and, of course, founded the American Red Cross in 1881, sixteen years later. The first courthouse was built in 1873. It is the only one of Kansas’ 105 counties to be named for a woman. Just look what your author did for those of you in Great Bend, that visit this website.

AND JUST

AND JUST

WHY WAS GREAT BEND NAMED GREAT BEND?

LOOK! SEE THE BEND IN THE BIG ARKANSAS RIVER? The Indians say huge herds of THOUSANDS OF wild Buffalo that gathered to drink water there.

But Clara Barton’s travels, were not limited to Kansas, nor to Europe, where she made arrangements to begin the American Red Cross, a few years later, but she made her way to just south of Atlanta, Georgia where 13,000 United States Soldiers, during the Civil War, died horrible deaths, from starvation and lack of medical treatment while 35,000 survivors of horrible unimaginable treatment were being forcefully held at the “now famous Andersonville Prison.”

Jim and his buddy don’t recollect his name, (it’s been over seventy years ago) had been harassing their Colonel, “politely” to help them get transferred to China that’s what the two thought; so they could be real Marines, and get away from pencil pushing. So, the Colonel took this opportunity and used his influence and had Jim and his buddy transferred to the Fleet Marine Force Pacific to help them get transferred to China. There was a delay on Oahu Hawaii, but Jim finally made it.

In order to appreciate the number of soldiers that were being held at the Andersonville prison, we will compare the figure being held to units during the second World War. when a typical Division of Infantry normally was fully served and Staffed, if the Division was made up of 18,000, usually men. Andersonville Prison was keeping under horrible conditions just under two divisions and two thirds of a division were dying or already dead.

In order to appreciate the number of soldiers that were being held at the Andersonville prison, we will compare the figure being held to units during the second World War. when a typical Division of Infantry normally was fully served and Staffed, if the Division was made up of 18,000, usually men. Andersonville Prison was keeping under horrible conditions just under two divisions and two thirds of a division were dying or already dead.

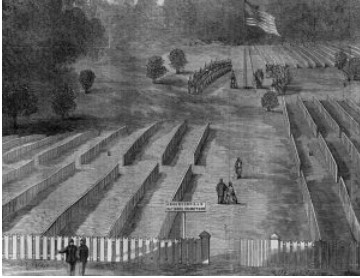

THOSE ARE ROWS OF TOMBSTONES YOU ARE LOOKING AT, NOT LIVE SOLDIERS STANDING AT ATTENTION. Soldiers taking part in the flag raising ceremony, are in formation closer to Clara Barton, who is doing the flag raising, near the bottom of the flagpole.

And Clara Barton, as was her nature, deliberately and with an attitude, walked right into this mess. She made it obvious by raising the flag at the cemetery.

And Clara Barton, as was her nature, deliberately and with an attitude, walked right into this mess. She made it obvious by raising the flag at the cemetery.

The picture of her doing it is so distant and blurred, that you cannot tell its Clara, but there are many witnesses to the event. One of those witnesses, a colonel in the Georgia military, Joel Griffin. Has an unincorporated town just outside Nashville, Tennessee named in his honor. The folks at the JOELTON post office selected the name. The picture of Joelton was taken at twilight and given by WTVF (channel 5) but if you look very closely, you can barely make out the skyline of downtown Nashville. Thirteen miles away. The photo helps you see it.

The Members of the post office, among many others had watched as a black man, Joel’s servant, pushed this aged veteran of the Civil War around several acres of property he owned in the area, in a wheelbarrow. Colonel Griffin was wounded in the battle of Petersburg, Virginia and was unable to walk around his property. Colonel Griffin, never, in the minds of most southerners, at that time, nor since, ever lived down the siege of Pittsburg, Georgia. The Union Army, under the direct control of Ulysses S Grant, Abraham Lincoln’s personal choice, was hot on the heels, of Robert E. Lee, who soon surrendered. Casualties, much of it from-hand-to-hand-combat-fighting, of course, were extremely high, on both sides.

In the preceding page the author made reference to Robert E Lee’s surrender to his counterpart in the Union Army, Ulysses S Grant. When General Lee, surrendered, so did the entire South.

Lee and Grant, both holding the highest rank in their respective armies, had known each other slightly during the Mexican War and exchanged awkward personal inquiries. Characteristically, Grant arrived in his muddy field uniform while Lee had turned out in full dress attire, complete with sash and sword.

Lee asked for the terms, and Grant hurriedly wrote them out.

“All officers and men were to be pardoned, and they would be sent home with their private property–most important, the horses, which could be used for a late spring planting.

Officers would keep their side arms, and Lee’s starving men would be given Union rations”.

The Surrender Meeting

“The Surrender” painting by Keith Rocco shows Generals Lee and Grant shaking hands near the end of the meeting.

April 9th, 1865, was near the end of the Civil War for General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

But for Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant and tens of thousands of Federal and Confederate troops fighting further south, the war stretched on for several more months.

After Appomattox, however, only the most zealous and desperate could pretend the Union was not already victorious and the Confederacy was destined to end.

For the rest of America, the war lingered through a series of surrenders and the capture of Jefferson Davis in the spring and summer, leading to many competing claims for the “true” end of the war. With each ending there was a new beginning into an uncertain peace and an even more uncertain movement for freedom and equality for the millions of African Americans who were finally free by law, though local practices ensured continued discrimination and slavery in other forms.

Contemporary historians like Dr. Elizabeth Varon in “Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the End of the Civil War” and Dr. Heather Cox Richardson in “West From Appomattox” have explored changes resulting from Appomattox. Appomattox led to the collapse of the Confederate government and the beginning of systematic “Reconstruction” across the entire South.

Lee’s General Order No. 9 may have been the beginning of the “Lost Cause” apologist movement that sought to erase the institution of slavery as a fundamental cause for secession and the war. Perhaps more than being an end or a beginning, the surrender at Appomattox should be viewed as an intersection of change.

To quote Joe Servis, a history teacher, at Appomattox County High School, in Georgia,

“Most events in human history rarely have neat and tidy beginnings and endings, and the surrender at Appomattox is no exception.

TRUER WORDS WERE NEVER SPOKEN, MR. SERVIS, AND, ALTHOUGH YOU “TEACH HISTORY” AND WE OLDER ONES, OFTEN TIMES, “BOAST OF LIVING IT.”

AS YOU WELL KNOW, THERE HAVE BEEN AT LEAST SIX MAJOR WARS FOUGHT BY THE UNITED STATES SINCE THE ONE INVOLVING “YOUR COUNTY, APPAMATOX COUNTY, GEORGIA,” THE CIVIL WAR.

David Rhodes was, involved that one, and came awfully close to giving his life.

In 1851, Indiana adopted a new constitution, and among its new clauses was one that prohibited blacks from immigrating to Indiana. The prohibition was intended to be a punishment to the slavery states.

Like several other northern states, Indiana lawmakers believed most free blacks were uneducated and ill-equipped to care for themselves. They believed since the South put them in that condition, the South should be responsible for the “burden” of caring for them.

This view, that the South should clean up its own mess, remained dominant even after the Civil War, and the clause in Indiana’s constitution was not repealed, or officially done away with, until the 20th century.

David’s state, Indiana, where David was born, and enlisted in the Union Army, did not condone slavery, but as Mr. Servis described, had a strange way of expressing it.

CONFEDERATE CAPTAIN HENRY WIRZ

Commandant of Andersonville Prison

We have already covered the story of David Rhodes, who was wounded and captured by the Confederates at the battle of Chickamauga and admitted to Andersonville. The prison was commanded by Captain Henry Wirz of the Confederate Army. Henry Wirz was the only man convicted for what would now be considered war crimes.’

Wirz was born in Zurich, Switzerland and was hanged in Washington, D.C.

November 10, 1865.

Birth Date:

11/25/1823

An official Photo of Wirz being hung.

An official Photo of Wirz being hung.

Camp Sumpter is the official name for the prison at Andersonville, Georgia, where David Rhodes, being loaded on the wagon with other dead prisoners, wiggled his toe showing he was alive, or at least someone thought he was alive, and David was unloaded from the wagon of dead union soldiers and sent to the hospital in Charleston to survive. Months later he recovered and was released from the Army.

We have written about that already.

Now it is told by a different person, ELIZA FRANCES ANDREWS, a plantationowner’s daughter with a different political approach.

Eliza Frances “Fanny” Andrews was born on August 10, 1840, in Washington, Georgia, the second daughter of Annulet Ball and Garnett Andrews, a Georgia superior court judge. Her father was a lawyer, judge, and plantation owner, possessing around two hundred slaves. Andrews grew up on the family estate, Haywood, the name of which she would later use in a pseudonym, “Elzey Hay” attended the local Ladies’ Seminary school, and later graduated among the first class of students from LaGrange Female College in Georgia in 1857. She was well-versed in literature, music, and the arts, and was conversant in both French and Latin.

Upon graduating “Fanny” had returned to live at home in the care of her family when the Southern states began to secede from the Union. Her father was notoriously outspoken against secession but, despite his views, three of his sons enlisted in the Confederate States Army and his daughters, too, believed in the rebellion. Thus, while Garnett Andrews refused to allow secessionist ideals to be voiced in his home, his daughters are said to have secretly made the first Confederate flag to fly over the courthouse in her hometown. Conflicting opinions with her father agitated and confused the young Andrews. Her father, who in the words of one biographer “helped his children to learn to love books and learning”, had begun suppressing her beliefs.

Upon graduating “Fanny” had returned to live at home in the care of her family when the Southern states began to secede from the Union. Her father was notoriously outspoken against secession but, despite his views, three of his sons enlisted in the Confederate States Army and his daughters, too, believed in the rebellion. Thus, while Garnett Andrews refused to allow secessionist ideals to be voiced in his home, his daughters are said to have secretly made the first Confederate flag to fly over the courthouse in her hometown. Conflicting opinions with her father agitated and confused the young Andrews. Her father, who in the words of one biographer “helped his children to learn to love books and learning”, had begun suppressing her beliefs.

Eliza Frances “Fanny” Andrews

None of this concerns David Rhodes and David’s great granddaughter Dana Chapman (later to be Setters.) But it lends credence to the above State Highway sign about Captain Wirz. Do you believe Eliza and the highway sign and what Eliza said about Wirz on that sign?

“YOU KNOW? NONE OF WHAT WE JUST WROTE”

STOPPED DAVID’S TOE FROM WIGGLING

David Wyrick Rhodes

1841 – 1927

First though, the author of “THE LADIES OF SETTERS LAKE”, would like for you to meet Joe Servis,

Where Do You Teach?

“Appomattox County Public Schools. I teach 10th Grade Modern World History and 11th Grade AP U.S. History at Appomattox County High School.

This is my 23rd year of teaching.

Please, give us your twitter-length philosophy of education. “History is complicated, so always assume there is more to the story. Encourage your students to question, seek out the facts, and never stop digging into a topic, even if the answers they find make them uncomfortable. The truest learning often happens outside of your comfort zone. What do you find to be the most challenging aspect of teaching social studies and the Civil War era?

Getting students to rethink their assumptions and get them to accept that what they have been taught may not be the whole story. Getting students to consider and evaluate ideas that put them outside of their comfort zone is hard, but I think that is where the best and most meaningful learning can happen.

Getting students to rethink their assumptions and get them to accept that what they have been taught may not be the whole story. Getting students to consider and evaluate ideas that put them outside of their comfort zone is hard, but I think that is where the best and most meaningful learning can happen.

Also, getting students to learn how to generalize concepts without falling into the trap of oversimplifying a topic so they can just memorize the “right” answer.

Which brings things right back to the little four room grade school, the Jordonia grade school, five miles outside Nashville Tennessee, where Jim and his brother Raymond, graduated from the eighth grade, in 1941.

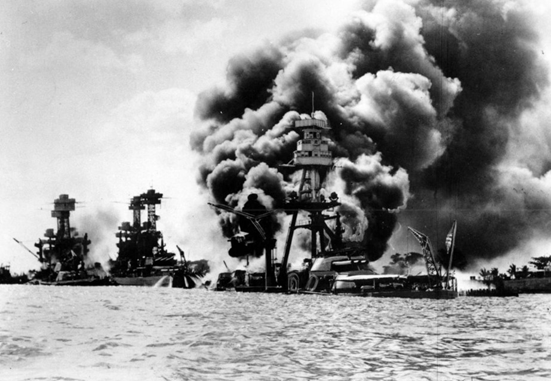

(The year made famous by the Japanese Admiral Yamamoto-led attack of Pearl Harbor nearly three quarters of a Century ago, on their brother, Harold’s birthday, December 7th)

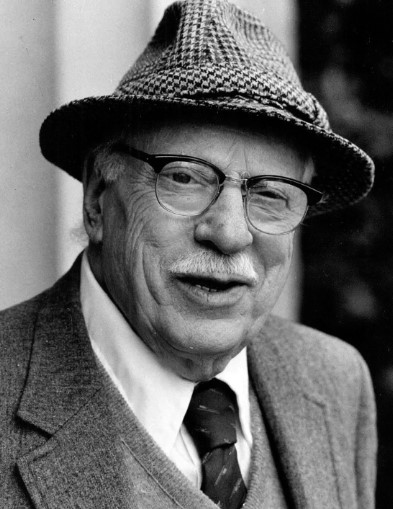

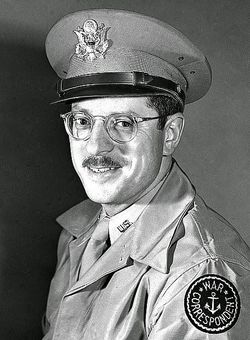

On 18 April 1943, a year and a half later, a flight of U.S. Army Air Corps P-38 fighters, ambushed and shot down the Japanese bomber carrying Admiral Yamamoto on an inspection tour in the Southwest Pacific. Yamamoto, who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor, was killed in the ambush.  The pilot who shot down and killed Yamamoto, Rex Barber, is pictured with his medals, in retirement, years later.

The pilot who shot down and killed Yamamoto, Rex Barber, is pictured with his medals, in retirement, years later.

David Rhode’s grandson, “Skinny” Rhodes (Bessie’s son) flew a P-38 against the Japanese in World War II.

David Rhode’s grandson, “Skinny” Rhodes (Bessie’s son) flew a P-38 against the Japanese in World War II.

The “JAPS”, as they were called by most of us, during WW-II, referred to the P-38, as the twin tailed devil, but so did the German Luftwaffe pilots.

The America’s top-scoring fighter ace of all time, Maj. Richard Bong, achieved all of his 40 aerial victories in P-38s, and the number two ace, Maj. Thomas B. McGuire, Jr., achieved most of his 38 kills in the P-38.

Richard Ira Bong was rightly nicknamed America’s “Ace of Aces” during WWII. He is credited with shooting down 40 Japanese aircraft during combat while flying a P-38 Lightning fighter in the Pacific, but it was the man holding his medals that killed Yamamoto and avenged PEARL HARBOR.

WORLD WAR TWO FIGHTER PLANE P-38, LIGHTNING

WORLD WAR TWO FIGHTER PLANE P-38, LIGHTNING

Bong was one of the most decorated American pilots of all time and was awarded the Medal of Honor by General Douglas MacArthur, in December 1944.

Bong, Loved Flying Low

Two years earlier, in 1942, near the beginning of the, then young, Bong’s career in the Army Air Corps Bong was called to General Kenney’s office and reprimanded for buzzing Market St. in San Francisco, and for flying a loop around the Golden Gate Bridge and flying low over the house of a fellow pilot who had just gotten married, blowing laundry off a neighbor’s clothesline. Bong was afraid he was going to lose his wings

Kenney wrote in his memoir that after asking Bong what it was like to fly low over Market St., he realized the young guy standing in front of him was the type of person the Army Air Force needed. He also told Bong to call the woman whose clean clothes were blown off her line and offer to help her with her laundry and Bong had to mow her yard.

On August 6, 1945, during World War II an American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first deployed atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The explosion immediately killed an estimated 80,000 people; tens of thousands more would later die of radiation exposure. Three days later, a second B-29 dropped another A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people. Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender in World War II in a on August 15, 1945, citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb.”

On August 6, 1945, during World War II an American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first deployed atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The explosion immediately killed an estimated 80,000 people; tens of thousands more would later die of radiation exposure. Three days later, a second B-29 dropped another A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people. Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender in World War II in a on August 15, 1945, citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb.”

Most of Americans had little or no idea about the horror those two atomic bombs created. The August 7th, 1945, morning Los Angeles Times led their morning paper with big headlines about it, but the editors failed to comprehend the enormity of the event, even sharing the HEADLINES with Major Bong’s death.

The crash of that experimental jet fighter and what it meant to the defense of America actually played second fiddle to the beginning of the new atomic age.

Now, we return to an earlier year of 1941, at Jordonia Grade school, where “Miss Alleyne Vaughn, the school’s Principal, and Jordonia’ s sixth grade teacher, Miss Cullum, the school’s only piano player, began putting together the eighth-grade graduation program.

James Robert Setters and his brother John Raymond Setters would be on the list of graduates. But because our country had been attacked at Pearl Harbor, by Japan, a few months earlier, the two teachers chose a national patriotic theme; rather than one with a Civil War atmosphere, which, had it not been for that attack at Pearl Harbor, a more appropriate theme.

See the young man without a pilgrim type hat on his head? That boy, Leon Carney, an eighth grader, was to play the role of George Washington, Leon was about six feet tall (Leon’s mother had not completed his costume yet) which is understandable.

Leon, as George Washington crossing the Delaware, was scheduled to carry one of the little boys, who played the role of an injured soldier. I don’t know how that worked out, because I was too busy trying to play the flute.

(Borrowed for the occasion.)

Raymond is standing on the right end, in the picture and I am on your left of that row. The littlest boy squatting in the picture was the hero of the night. Leon had no trouble carrying him. It could have been a girl. The school did not have a stage. So, we put on the BIG SHOW in the Jordonia Methodist Church, next door.

Esther Setters, our mother. made our costumes on her day off from the shirt plant.

On August 6, 1945, four years later, during World War II, an American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first deployed atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

The explosion immediately killed an estimated 80,000 people; tens of thousands more would later die of radiation exposure. Three days later, a second B-29 dropped another A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people. Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender in World War II in a on August 15th, 1945. citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb.”

Major Bong General MacArthur General Kenney

Hirohito had seemingly forgotten or did not know (which is highly unlikely) about the rape of Nanking or Nanjing China, then the Capital of China, in 1937 during that horrible conflict between China and Japan, or the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor.

Hirohito had seemingly forgotten or did not know (which is highly unlikely) about the rape of Nanking or Nanjing China, then the Capital of China, in 1937 during that horrible conflict between China and Japan, or the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor.

If he did know, about the two, and one of them so nightmarish, the normal person’s mind has problems dealing with it, The emperor simply ignored them.

And the worst of the two, unfortunately, was not the attack on Pearl Harbor (in your Author’s opinion.)

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese military had launched a surprise attack on the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

On December 8, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt asked Congress for and received a declaration of war against Japan. On December 11, Germany and Italy, allied with Japan, declared war on the U.S.

Since early 1941 the U.S. had been supplying Great Britain in its fight against the Nazis. It had also been pressuring Japan to halt its military expansion in Asia and the Pacific.

With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. could no longer avoid an active fight. The United States had entered World War II on December 6, 1941, the U.S. intercepted a Japanese message that inquired about ship movements and berthing positions at Pearl Harbor. The cryptologist gave the message to her superior who said he would get back to her on Monday, December 8.

On Sunday, December 7, a radar operator on Oahu saw a large group of airplanes on his screen heading toward the island. He called his superior who told him it was probably a group of U.S. B-17 bombers and not to worry about it. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor began at 7:55 that morning. The entire attack took only one hour and 15 minutes.

Captain Mitsuo Fuchida sent the code message, “Tora, Tora, Tora,” to the Japanese fleet after flying over Oahu to indicate the Americans had been caught by surprise.

The Japanese had planned to give the U.S. a declaration of war before the attack began, so they would not violate the first article of the Hague Convention of 1907, but the message was delayed and not relayed to U.S. officials in Washington until the attack was already in progress.

The Japanese strike force consisted of 353 aircraft launched from four heavy carriers. These included 40 torpedo planes, 103 level bombers, 131 dive-bombers, and 79 fighters. The attack also consisted of two heavy cruisers, 35 submarines, two light cruisers, nine oilers, two battleships, and 11 destroyers.

The attack killed 2,403 U.S. personnel, including 68 civilians, and destroyed or damaged 19 U.S. Navy ships, including 8 battleships. The three aircraft carriers of the U.S. Pacific Fleet were out to sea on maneuvers. The Japanese were unable to locate them and were forced to return home with the U.S. carrier fleet intact.

The battleship USS Arizona remains sunken in Pearl Harbor with its crew onboard. Half of the dead at Pearl Harbor were on the Arizona. A United States flag flies above the sunken battleship, which serves as a memorial to all Americans who died in the attack.

Prior to the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the U.S. Marines attacked the Japanese island of Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945. In its 36 days of combat on Iwo Jima, the Fifth Marine Amphibious Corps made up of the Fifth Division, what was left of the Third and Fourth Divisions, assaulted Iwo Jima, The war strategists

said they needed the island of Iwo Jima to provide emergency landing fields for the B-29s that were destined to bomb Japan’s homeland.

The defenders lost, and nearly all were killed, approximately 22,000 Japanese soldiers and sailors, The entire number of defenders under the Command of Japanese General Tadamichi Kuribay.

The assault units of the Marine corps—Marines and organic Navy personnel—sustained 24,053 casualties, by far the highest single-action losses in Marine Corps history.

Though most of the American dead were recovered in 1948, some 280 U.S. Marines — not including pilots and those lost at sea — are still missing from the Iwo Jima campaign. Many of them died in caves or were buried by explosions.

The cost to take Iwo Jima was staggering. And the reason for it’s being an important conquest has been questioned.

The cost to take Iwo Jima was staggering. And the reason for it’s being an important conquest has been questioned.

There may be a few adults in the United States who have not seen this picture of the Flag Raising on Mount Suribachi on that island. It was taken by Pulitzer Prize winner Joe John Rosenthal. But have they met Rosenthal? Chances are rare that they have.

The author would be pleased to introduce him, but not as a young man, necessarily, but as he appeared just before he died at the age of ninety-four, in 2006. Joe had lived for sixty-one years after he took that picture.

He made only a few dollars from having taken the most famous picture of the entire World War Two.

The son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, Rosenthal wore thick glasses and was rejected by the Army because of his poor eyesight. In 1944, when he was 33, he was hired by the Associated Press to cover the Pacific Theater as a war photographer.

He was right alongside the Marines when they landed on Iwo Jima, a small volcanic island not far from the Japanese mainland.

After four days of intense fighting, he heard the Marines were going to raise a flag on Mt. Suribachi. He climbed the 550-foot-high peak to try to capture the triumphant moment with his camera.

Because he was only 5-foot-5, the diminutive, mustached photographer stacked up some stones and sandbags to get a better angle on the flag raising, which happened so quickly that he only had time to snap off one shot. It just happened to be the perfect one.

Whenever he was praised for his famous photo after the war, Rosenthal liked to say, “I took the picture, the Marines took Iwo Jima.