Quite often in our story, THE LADIES OF THE LAKE, we include someone who either, never heard of Setters Lake, or of Leander, or any of the many problems or blessings associated with the Lake or Leander. But now, we will spend time with someone who was not just aware of both, but a person who owned, the Lake for a while. And so, we welcome into the Ladies of the Lake, our story, the person who was responsible for Leander’s committal into the poor house, just before he died in 1932. Can such a thing be possible? This pillar of the community dying in what was then known as, the Poor House? Let us discover as you read the following pages just who was responsible and why that decision was made.

Quite often in our story, THE LADIES OF THE LAKE, we include someone who either, never heard of Setters Lake, or of Leander, or any of the many problems or blessings associated with the Lake or Leander. But now, we will spend time with someone who was not just aware of both, but a person who owned, the Lake for a while. And so, we welcome into the Ladies of the Lake, our story, the person who was responsible for Leander’s committal into the poor house, just before he died in 1932. Can such a thing be possible? This pillar of the community dying in what was then known as, the Poor House? Let us discover as you read the following pages just who was responsible and why that decision was made.

LET YOU BE WARNED THOUGH, THAT THIS IS A TRUE STORY OF A FACTUAL SERIES OF EVENTS THAT OFTEN TIMES WILL NOT BE EASILY FOLLOWED AND SEQUENTIALLY NOT POSITIONED THE WAY YOU THINK IT SHOULD BE

You are gazing into the eyes of Bertha, Leander’s granddaughter. The picture was taken in 1919. If you think her expression reflects sadness, there is a reason. And we are all set to tell you why she has that sad expression. Bertha follows the same lineage as does the author of this story, Jim Setters. Bertha’s father was James Madison Setters, one of the two sons of Leander. James was the namesake of the author, Jim. James, the grandfather of Jim, died in Nashville, when Jim, the author was about four and a half years old, and about nine months before Leander died in April of 1932. So, how does this granddaughter fit into the life of Leander and into the Lake? In many, many ways, really!

Author’s note: When father and son and even the grandfather have the same first names it is tough getting all of the family properly identified. There were four John Marshall Setters in this family (but two of them died at birth) There is still a John Marshall Setters living though. You’ll be reading, or already have read about him. His great-grandfather, my father, John Marshall Setters died before my brother’s grandson was born.

You noticed her nephew, Jim the author of THE LADIES, and one of a family who, oftentimes benefited from Bertha’s unselfish side, did not give you Bertha’s last name. Just Bertha, Leander’s granddaughter. The reason? Well, she really had five last names, but Jim and his two brothers, her nephews, always referred to her as “Auntie”.

Bertha was born on Monday, June 13th. in Boone County, Kentucky in 1887 to James Madison Setters and Carrie Belle Marshall Riddel. Notice, the author, Carrie’s grandson, Jim, put part of his grandmother’s name, Marshall, in italics and for good reason, which we will explain, later.

Bertha was married a total of four times, but was the mother of only one child, a boy, and this part of our story concerns, this little boy, plus two other boys in the neighborhood and a lot of other people. Let us begin on a warm Thursday afternoon in Nashville, Tennessee on June 12th, 1919, more than a century ago. Bertha was looking forward Friday to celebrate her 32nd birthday.

Bertha Forte, Leander Setters’ granddaughter, used the streetcar to commute to her office in a big insurance company in downtown Nashville, at Fourth and Union. The weather was warm that Thursday afternoon and Bertha had good reason to be happy. She left the office and was looking forward to reaching her parent’s house and her twelve-year old son.

The war was over, and we won; her brother John had been released honorably just two weeks earlier and had survived the trenches of France. Her husband, Glister Forte, was alive and well. But he was still in France, soon to come home. Her brother was home. Bertha didn’t know it then, but the trenches came home with John and he, like so many others, never quite got out of them. Everyone in her family, as far as she knew, was in good health. Her grandfather, Leander, was seventy-nine years old and seemingly also fit as a fiddle. Two years ago, Bertha had helped her granddad make out his will. She was not actually named in the will, and she was not particularly happy about what Leander was leaving for Aleatha, her step-grandmother.

The war was over, and we won; her brother John had been released honorably just two weeks earlier and had survived the trenches of France. Her husband, Glister Forte, was alive and well. But he was still in France, soon to come home. Her brother was home. Bertha didn’t know it then, but the trenches came home with John and he, like so many others, never quite got out of them. Everyone in her family, as far as she knew, was in good health. Her grandfather, Leander, was seventy-nine years old and seemingly also fit as a fiddle. Two years ago, Bertha had helped her granddad make out his will. She was not actually named in the will, and she was not particularly happy about what Leander was leaving for Aleatha, her step-grandmother.

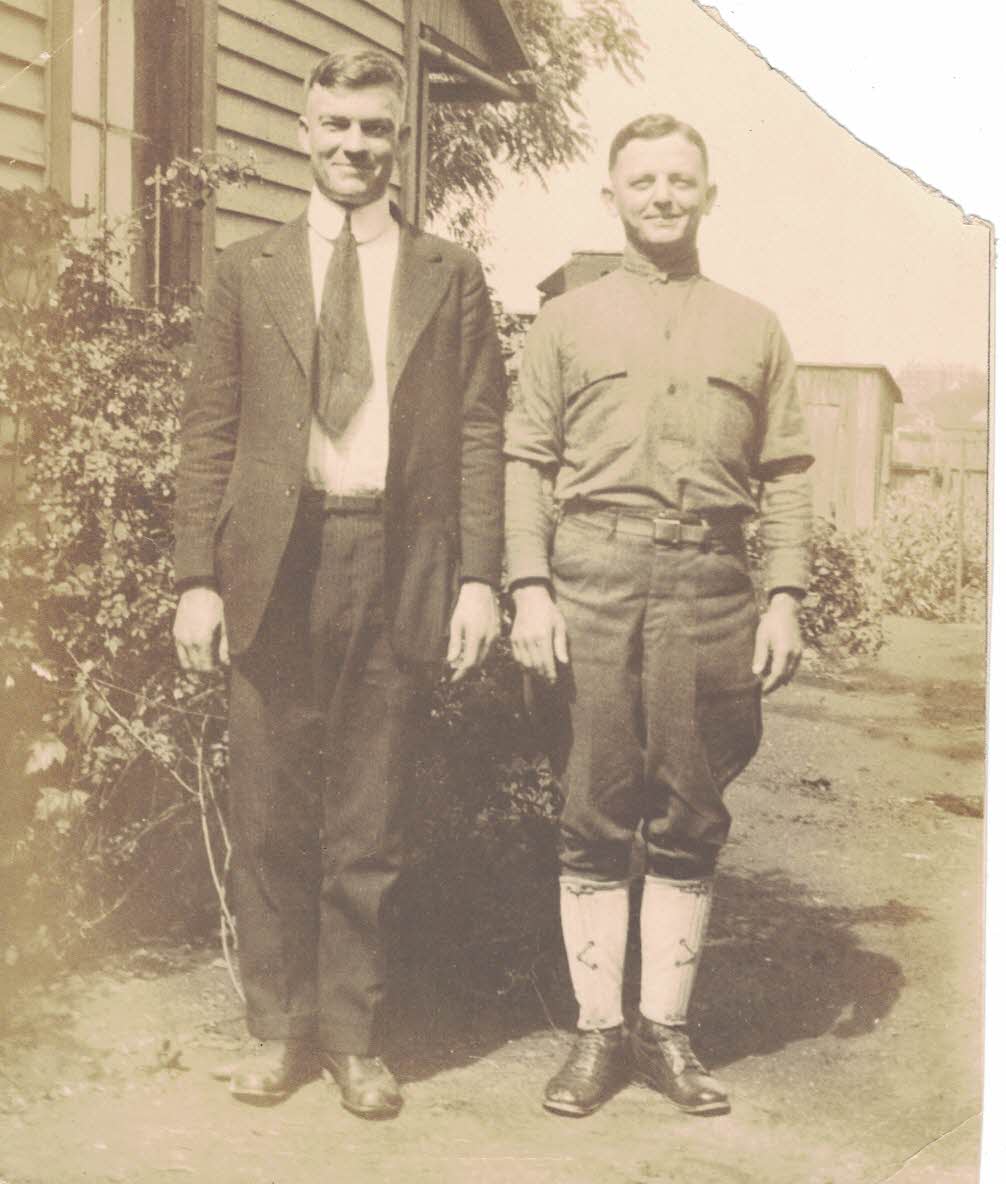

John Setters Glister Forte

Bertha was just three years old when her real grandmother Louisa died. Aleatha was not her favorite person, but it was not as though Aleatha had barged into her life. She, by this time, however, was aware that Aleatha married Leander before the grass began to grow on the grave of Bertha’s real grandmother; literally. One hundred forty-one days after Louisa was buried, Leander and Aletha married, and in that time of the year, from the 4th of July to October 26th, grass is not apt to sprout and grow. In the meantime, Bertha and her son were living with her mother Carrie and her father Jim, Leander Setters’ son. It was a small house at 1822 18th avenue North the actual end of the city limits boundary of Nashville. The street was still gravel. We’ll show you a picture of what we believe is the actual house in a bit.

Bertha had a good job. She was 31 years old, born in 1887 just seven months after the grand opening ceremonies of the Statue of Liberty in New York, and five months before the death, by tuberculosis, of the famed western gunfighter Doc Holiday. Doc Holiday was an accomplished dentist by the way. Bertha was born ten years before another dentist, 37-year-old William Morrison, in Nashville, Tn., invented cotton candy; (originally named Fairy Floss). What he and another guy invented was the machine that spun the candy.

Bertha had a good job. She was 31 years old, born in 1887 just seven months after the grand opening ceremonies of the Statue of Liberty in New York, and five months before the death, by tuberculosis, of the famed western gunfighter Doc Holiday. Doc Holiday was an accomplished dentist by the way. Bertha was born ten years before another dentist, 37-year-old William Morrison, in Nashville, Tn., invented cotton candy; (originally named Fairy Floss). What he and another guy invented was the machine that spun the candy.

When Bertha was born, the Eifel Tower in Paris looked like this, just barely being built. On this day in 1919, June 12th, Bertha was the mother of a healthy twelve-year old boy but, according to a much told and retold rumor, her husband and father of her son had died when the boy was just two years old. True? Not really. Even the 1910 census shows her as a widow. But this was not the case.

The fact was, her husband Forest Cowan Rice, her son’s father, did not die until April of 1966, more than half a century after the 1910 census. Forest Rice died in Cincinnati just across the Ohio River from Boone County where he was born 81 years earlier. After he and Bertha were divorced, around 1908, he married again to a woman named Edna Burkhardt. She left him a widower in 1949.

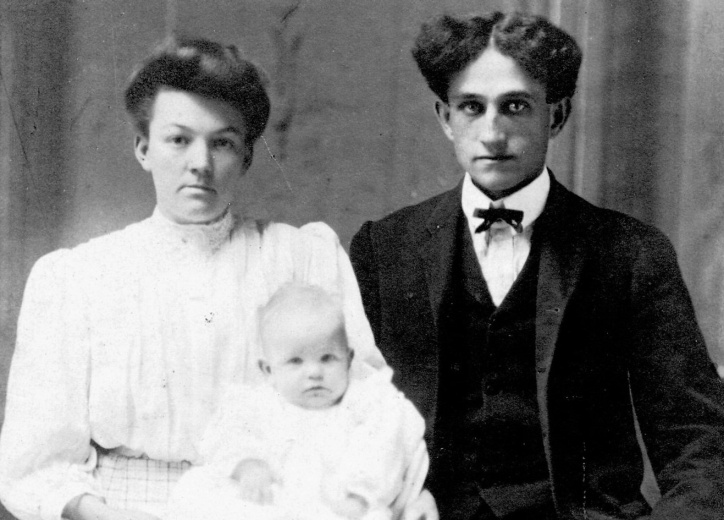

Bertha holding baby Lloyd sitting with her husband, the baby’s father,

Bertha holding baby Lloyd sitting with her husband, the baby’s father,

Forest Rice, when they lived in Kentucky in 1908.

Life was not easy in 1910 for a single mother. It would be another ten years before women could even vote. But in those ten years, Bertha would divorce this man, marry another that she would also divorce, she would bury her son and gain a niece that she would despise.

One hundred six years later, in 2016, a much controversial United States Presidential election saw a woman win by more than two and a half million popular votes but lose the Electoral College vote to a man. In Bertha’s earlier years women were, according to one of the ladies who fought for women’s rights, just a little more than toys for men.

If you were to ask the wife of one of Bertha’s three nephews about one hundred years later, Bertha was not a toy. More like a witch. At least when Bertha became an old lady. We’ll tell you about that in a little while.

In 1912 Bertha’s life changed. On July 2nd, 1912, a marriage license was issued for Bertha and Glister Forte. The ceremony took place two days later, on July fourth. The next day was Bertha’s brother John’s twentieth birthday. Five years later John and Glister would be sent to Europe to fight against Germany in World War One. Glister was Catholic, when he died, he was buried in the cemetery at the back of the only Catholic Church, in Leander’s neighborhood, The St. Lawrence. The St. Lawrence Catholic church was established in 1885, on what was then the Clarksville Highway.

Confessions began there three years before Leander left Kentucky, in 1888. Glister’s grave is a mile from Aleatha’ s. Hers is in a cemetery behind a Methodist Church, at Bear Hollow Road and the Clarksville Highway. Leander’s great grandson, John Raymond Setters suffered a fatal aneurism at his home on Bear Hollow Road less than a mile from Aleatha’s grave in 2018.

July turned out to be a busy month in the history of the Setters clan. Leander’s father, George Washington Jordan, died July 24th in 1885. Bertha’s brother, John, was born July 5th, 1892, just two years after their grandmother, Louisa, died on July 4th, 1890. Bertha was married the second time on July 2nd, 1912. Then forty-two years after the marriage license was issued, John’s grandson, John Steven, was born July 2, 1954, in Wichita, Kansas. July 23rd, 1988, John Steven was married to a Canadian nurse in a wedding ceremony held at the Navy Submarine Chapel at Pearl Harbor Hawaii.

July turned out to be a busy month in the history of the Setters clan. Leander’s father, George Washington Jordan, died July 24th in 1885. Bertha’s brother, John, was born July 5th, 1892, just two years after their grandmother, Louisa, died on July 4th, 1890. Bertha was married the second time on July 2nd, 1912. Then forty-two years after the marriage license was issued, John’s grandson, John Steven, was born July 2, 1954, in Wichita, Kansas. July 23rd, 1988, John Steven was married to a Canadian nurse in a wedding ceremony held at the Navy Submarine Chapel at Pearl Harbor Hawaii.

But this, the 12th day of June 1919, was going to be a bad afternoon for three families in Nashville. And Bertha was not to be spared some of the agony that lay ahead.

Bertha walked from the office building to the streetcar transfer station, boarded the car and breathed a sigh of relief. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, where Bertha worked all of her adult life, was located at 4th and Union in the heart of Downtown Nashville.

In another part of our story, we learn of another man, Morris Frank, who had an office in that same building ten years later. He was a Vanderbilt student, was blind, and had an office and work location in that building for two years. As has been pointed out in other parts of our story, it is rather obvious Bertha more than likely knew him. The building only had one elevator and most of the office personnel used it. Probably many people in Nashville would see him with Buddy, his well-trained guide dog. Up, until that time dogs were not used to help blind people.

Bertha’s nephew, Jim, sang with a little band in 1945 with a totally blind piano player and nearly blind drummer and they struggled around as best they could without a dog. You will learn more about this young blind man later in our story. But in 1919, when little was known to correct retina problems, cataracts and glaucoma, there were many more blind people than today……at least in America. This problem is mentioned simply to identify the culture of the time.

And actually, many of the blind simply did as best they could, humbly standing on the corner waiting for the light to turn red to stop traffic and then hoping that some kind good Samaritan would take him or her by the arm and lead them across the street. Many citizens of that time would not become involved.

We think there are lots of folks who are prejudicial now, in the twenties it was rampant, and being inherited by children. The blacks were the more discriminated against then, followed by the Jews and any other people whose hair and skin was different from the Anglo Saxon. Even the women were denied the right to vote until about 1921. So, blind people were just another group to keep at arm’s length. Even the drunks were given more respect than the Jewish people. On Little Marrowbone creek it was a guy named Benny pignolia, speaking broken English, a friend of the Cochin family or perhaps a relative who used to visit from Italy. But fortunately, for him at least, about three miles from Setters Lake was the Germantown Hill; so, named because the area was home to so many German immigrants. There were also many Italian immigrants. That is why there was so much good, tasty wine made there.

Many of the Italians had beautiful grape vineyards……and so did the German folks. Somehow, in spite of how ignorant many of the non-immigrants were, it worked out very well. The Idas, Zimmerle’s, Fortes, Conchin, Schnupps, and the non-immigrants blended in very well. There was always enough wine, garlic, homebrew and moonshine to go around. And it did. The wine making existed on for another sixty years, at least.

One pleasant afternoon in the early thirties John and Esther Setters were visiting the Forte family on the Forte Road. The three Setters boys, Harold, Raymond and James were outside playing. They found a big jug of wine in the workshop and all three, James was about five or six years old, got a little tipsy drinking the delicious, sweet Italian/German wine. Their parents didn’t notice since at their ages, Harold was about ten, boys are about half-way out of their heads anyway.

What happened the time Bertha rode in that streetcar, although at the time she was not aware that it was happening, was burned into her memory for the rest of her life. Carrie Setters, Leander’s daughter-in-law, and the boy’s grandmother was inside the Setters home preparing dinner. Bertha would be home soon, and her grandson would be hungry. She had just checked on him as he played out under a big tree in the front yard.

Two twelve-year old boys and a thirteen-year- old boy were about to die. Two from drowning, one by hanging. All accidentally and because of normal twelve-year old boy type carelessness. Instead of watching their boys enjoy the freedom of summer and no school, these mothers and fathers, three households, were plunged into the deepest of all despair; having to bury their children. One of the twelve-year old boys, Franklin Powell, was with a group ready to challenge the swift muddy waters of the Cumberland River. Their parents had warned them not to go into the river, but Franklin did. He floundered around, perhaps hit by cramps, and began yelling for help. His friend, thirteen-year-old Joe Creswell, they say, without hesitation, jumped into the swift muddy water and swam out to help him. They thrashed around some, then hugged one another, and sank into the murky water and disappeared.

After several minutes of trying to find them, the other boys gave up. They then ran the several blocks to tell the parents what had happened. At that point in time there were no organized official search and rescue efforts available. First responders were not yet just a two-way radio call away. And there were no two-way radios then either.

Any form of instant communication was all but nonexistent. As it happened, the bodies of the two boys were found by their neighbors who risked their lives in the muddy waters of the Cumberland River. The six hundred eighty-eight-mile-long river, at one time named Riviere des Chaouanons, or “river of the Shawnee,” had claimed two more of the many young men and boys who had challenged it: including no doubt some careless Shawnee braves.

The scene today is near Interstate 24. Joe Creswell would be pleased to know that a school, where three of the great-grandsons of Leander Setters attended twenty years later at Bordeaux, a mile or so away, would be named the Creswell School. It is located on the same site as Cumberland High School. All but the gymnasium has been replaced by a new building. But the school is not named after Joe, it was named after an African American whose accomplishments in education brought about the tribute. Pity, there seems to be nothing remaining as a memorial to a little boy who gave his life in a vein effort to save the life of a friend.

Just the previous Sunday, only four days earlier, there had been another drama in the water of another river in the Nashville area, the Harpeth, one of the Cumberland’s tributaries, and as was the case with our two young boys, there was a hero. But he was a grown man, Dr. George H. Donaldson. George was born fifty-nine years earlier in Kentucky. He was returned to his family cemetery in Kentucky just about the time the boys were taken out of the Cumberland June 12th. He drowned Sunday, they drowned Thursday.

But now we focus on a small front yard about one mile away from the drowning of Joe and Franklin to the front yard of Jim and Carrie Setters, on eighteenth avenue north. A twelve-year old boy was playing in the small front yard of the home of James and Carrie Setters. His name was James Lloyd Rice. He was born in Kentucky the year his great-grandfather began scooping out the Lake which by now was full of water about ten miles from that front yard where that little boy was playing. His mother, Bertha, who brought Lloyd to Nashville in 1910, would be home soon, his grandmother was in the house preparing supper. There are conflicting stories about his father, some say he had died, and some say he left the family. Lloyd’s stepfather was in the Army and still overseas. He had grown close to his stepdad before World War One took Glister Forte overseas, where he still was that fateful afternoon. Lloyd was four years old when his mother, who was shown as a widow in the 1910 census, married Glister. That marriage would soon end in divorce.

A photograph of the two when Lloyd was about eight years old indicates the two had a good relationship. The picture was taken on the bank of the Cumberland River, not far from where the tragic drowning in 1919 would happen.

Both of Glister’s parents were immigrants, his dad from Germany and his mother from Italy.

Both of Glister’s parents were immigrants, his dad from Germany and his mother from Italy.

Lloyd’s last name was never changed up until his death indicating Glister never initiated an adoption. Our culture at that time was somewhat opposed to legal details. Another version of that relationship was given by another one-time member of the family, the little boy’s uncle John’s ex-wife. She quoted Glister as having said, before going overseas during World War One, that he would rather face the Germans than to spend any more time with that brat. But there was bad blood between Ruby Setters and the rest of the Setters family. Most felt a bad attitude contributed to her making all that up. But who really knows? Lloyd’s uncle John was one of Ruby’s four husbands. And she had divorced him just a few weeks after he was discharged from the Army. Carrie had given James Lloyd a quick glance playing in her front yard and had no idea what he was doing or contemplating on doing.

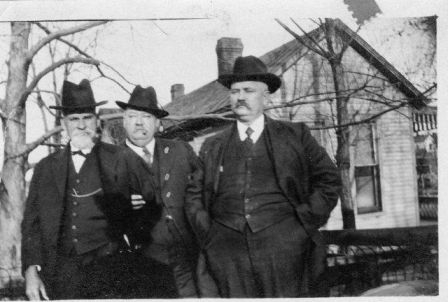

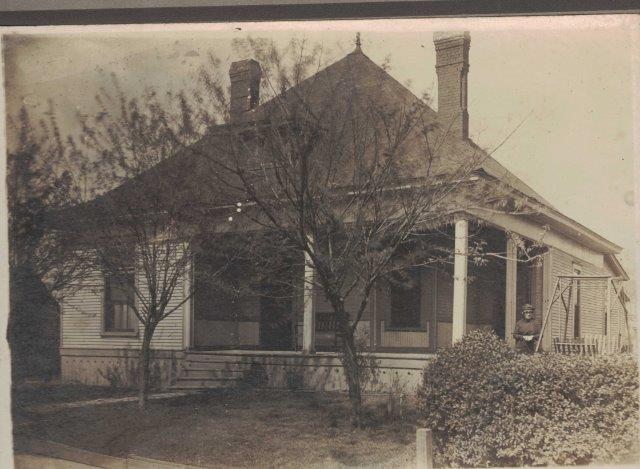

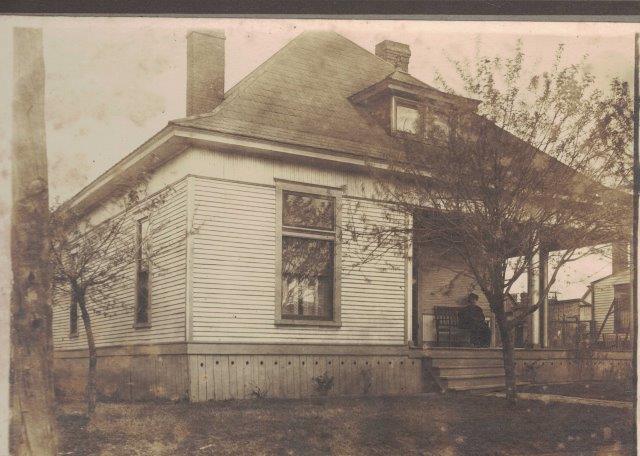

The author does not claim that this little house is the same1822 18th avenue North, the Setters home in our story. The name of 18th Avenue was changed to Dr. D. B. Todd, Jr. Boulevard 63 years later, after Lloyd’s tragedy, to honor a black surgeon and Meharry Medical College Surgical Professor. The street view photo service identifies this small isolated little house, resembling older photos, as 1822 D.B. Todd jr. Boulevard. Jim Setters your author asks you to go ahead one page to the picture of the three generations, Leander, James (Lloyd’s grandfather, and Bill Setters. The photo is of them standing in the front yard and near the site of the tragedy. One of the two pictures even has Lloyd with the three.

The author does not claim that this little house is the same1822 18th avenue North, the Setters home in our story. The name of 18th Avenue was changed to Dr. D. B. Todd, Jr. Boulevard 63 years later, after Lloyd’s tragedy, to honor a black surgeon and Meharry Medical College Surgical Professor. The street view photo service identifies this small isolated little house, resembling older photos, as 1822 D.B. Todd jr. Boulevard. Jim Setters your author asks you to go ahead one page to the picture of the three generations, Leander, James (Lloyd’s grandfather, and Bill Setters. The photo is of them standing in the front yard and near the site of the tragedy. One of the two pictures even has Lloyd with the three.

Look at the little house with Leander and his two sons. Look at the style, then observe the type of building above. Even the most doubtful cannot deny the similarity.

James Lloyd was the name of Bertha’s 12 year old son. His middle name was used, no doubt, because they lived with Bertha’s folks and the boy’s grandfather was also James. Lloyd had a rope he wanted to use to make a swing. But climbing up to that limb, about ten feet off the ground, was difficult especially trying to carry a coil of rope. Lloyd did, as they say, the wrong thing at the wrong time, and draped it around his neck and climbed up the tree.

One would hope at that busy time of the afternoon an adult would be walking by or watching from a front porch and interrupt what could, and did, turn into a tragedy.

Lloyd, without taking the time to remove the rope began tying it to the limb. He lost his balance and fell. The rope was tied securely to the limb leaving just enough slack to allow Lloyd’s feet to hit the ground but not enough to keep him from getting a jerk that broke his neck and back. The boy’s limp body was taken into the house, but he never regained  consciousness.

consciousness.

Or as the newspaper the next morning expressed it, “and the spirit had fled before the doctor could be summoned.” The fatal tree is just to the left of Lloyd’s grandfather’s left shoulder, his elbow looks like it is touching it. But it isn’t. Bertha soon bought the house at 1116 Buchannan, about half a mile away. But she often had to drive right past that tree. She often, in later years, bought cookies for her brothers three sons at a bakery just a few feet away from her son’s fatal fall.

James Lloyd Rice became the third boy in Nashville to die that afternoon. Little if anything at all is known about how Bertha learned of the death of her son. Any one of several possibilities would be bad. Did someone meet her when she got off the streetcar a block or so away from home? Did they wait until she saw the gathering of neighbors and official vehicles? And what did they say to her? Just a short while after her son fell from that tree and the snap of the rope ended his life she was at his side. But it was too late.

No one survives that spent any time with Carrie after the tragedy in any kind of discussion about the event. All we know is that she stepped out onto the porch to draw some water and saw her lifeless grandson’s head held up off the ground in the loop of rope. He was left in her charge. It was her responsibility to keep him safe. She failed to do that. We all know that trying to keep a twelve-year old boy from hurting himself is all but impossible. Others may have forgiven her, but did she? We’ll never know.

Carrie had already, in a way, lost another grandchild, a granddaughter. The little girl did not die, she was simply kept away from any of the Setters. Carrie’s son, John, was the father but the marriage was short lived. Bad feelings in the family had already begun and Carrie died eleven years later, not really ever enjoying the joy of watching any of her grandchildren growing into adults. We do know that this forty-nine-year-old woman was rejoicing on June third about her son having come home from a dreadful war and now, nine days later, discovered her twelve-year old grand-son, dead, hanging by a rope in a tree. In her own front yard. The boy’s first name was James. The first name of Carrie’s husband, the boys’ grandfather.

The funeral, complete with hearse and assorted support vehicles and published notices was paid by Bertha on, strangely enough the date of Lloyd’s death, June 12, 1919. At least that was the date of the funeral home receipt. The total cost was $158.90. Compared to the average funeral cost in 2017 of over $6,000.

But Bertha had to pay to transport the casket to the cemetery in Kentucky. Like Dr. Donaldson, Lloyd entered life in Kentucky and was buried in Kentucky. By the way, of the $158.90 funeral expense, $100.00 was for the casket.

Lloyd’s death came exactly four months before his fraternal grandfather. Erastus

Warren Rice, Sr., who was born the same year as Leander Setters. Erastus died on the eleventh of November. He died almost to the hour, twelve years before the birth of a baby in Iowa who would marry one of Bertha’s nephews.

Lloyd was buried in Walton, Kentucky, where he was born twelve years earlier. Bertha never had another child. But she played a very supportive role in the lives of her three nephews. And she held onto her grand-father’s lake for over forty years after Leander died, thirteen years after that fateful fall from the tree. She and Glister were still married a year later, but she would be married two more times before she left this world.

For Leander, June 12th, 1919, was also a sad day. He had come to Nashville thirty-one years earlier to cut thousands of trees for railroad ties. Now he had lost his first great-grandson. There was just one tree too many. A decade later, shortly after Carrie died, Bertha was sitting with one of her nephews. The two were discussing something and for some reason the little boy said, “I wish grandma had not died” or words to that effect. He was uncomfortable when his “Auntie” softly cried and said, “Me too.” He had never seen her cry before. Nor, had many others.

That summer of 1919 in Nashville was not all bad, however. Not far from the house on eighteenth avenue lived Charles and Myrtle Deason. Charles was a brakeman for the Tennessee Central Railroad, the same railway that hired Leander to provide cross ties. A few weeks after Lloyd died, on August 30th, Myrtle gave birth to a daughter. They named her Ellen. You will know her best by her professional name, Kitty Wells. One of the few super-stars of country music, born in Nashville. Kitty’s parents were both musicians and at age of 18, she married a musician.

A honky-tonk-country music style pianist Del Wood was also born in Nashville. Del and Kitty died after suffering strokes. Neither used their real names as performers. Kitty was ninety-two years of age at death.

A honky-tonk-country music style pianist Del Wood was also born in Nashville. Del and Kitty died after suffering strokes. Neither used their real names as performers. Kitty was ninety-two years of age at death.

Matured glamorous

aDELaide Hendricks HazleWOOD

Del, who died from a stroke on Esther Setters’ birthday, October third, was the same age at death as Esther, sixty-nine.

KITTY WELLS

Del had worked in a music store while playing the piano professionally and noticed that most of the piano music sold was to women and that women usually chose male pianists. So, she selected a name that could be either!

And, on that tragic day of June 12th, 1919, just a four and a half-hour drive away, by today’s driving, there was a little four-month-old baby boy named Ernest Jennings Ford, born in Bristol Tennessee. He was born just four months before Lloyd tried to take the rope up that tree. In just 25 years Ernest became a bombardier on an Air Force B-29 and flew missions over Japan in World War II. You know him as Tennessee Ernie Ford.

In seventy-one years from the time that Lloyd lay lifeless in the front yard of his grandparents, Ernest would be inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. Among his many big hits was “Sixteen Tons”. He died just one year after the honor was given him, suffering from alcohol addiction. Death came shortly after he had dinner at the White House with George H. W. Bush. Offstage, both Ford and wife Betty contended with serious alcohol problems; Betty had the problem since the 1950s. They had more to talk about than just music; President Bush also flew in World War II, as the pilot of a Naval dive bomber.

Though Ernie’s drinking worsened in the 60s, he worked continuously, seemingly unaffected by his heavy intake of whiskey. By the 1970s, however, it had begun to take an increasing toll on his health and ability to sing. After Betty’s (Mrs. Ford) substance abuse-related death in 1989, Ernie’s liver problems, diagnosed years earlier, became more apparent, but he refused to reduce his drinking despite repeated doctors’ warnings.

This was an eventful summer in Tennessee. It’s unclear whether it was Bertha or her parents, Jim and Carrie, who, later, bought the house at the corner of 12th and Buchanan. Both were financial capable. The house is just a few blocks from where the tragedy occurred. On June 12th. But that tree was out of sight.

The address, 1116 Buchanan, became the pivot of many incidents in the Setters family. That address is given on the death certificates of Jim and Carrie, their son John. It is also on the birth certificate of John Raymond Setters, John and Esther’s second son, and their third son James. If old documents could be found, it would be the reference address for many medical incidents involving the Setters family. It was used in order to meet the qualification for treatments at the Nashville General Hospital. There was no money for things like that. And there was certainly no health insurance.

The house that was once the Oasis for the Setters family is now gone and replaced by a concrete block structure and surrounded by commercial buildings. Strangely enough, the service station across the street is the same as it was then, although the building is vacant.

There is a strong urge in all of us to go home. Bertha, as it was with the other Ladies of the Lake, did not consider the Lake on Little Marrowbone, her home. But she had strong feelings for it. She often made the comment about either going or about something happening down on the creek. Her home was in Kentucky. There she grew into an adult: it was there she gave birth to Lloyd. It was there that she was the big sister to John Setters as they played in the woods nearby their home. Bertha was five years older than John. He would always be her little brother.

There are not too many of us who can say we were born the year that Sears became Sears and Roebuck, but Bertha could. In 1886 Richard W. Sears founded the R.W. Sears Watch Company in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to sell watches by mail order. He relocated his business to Chicago in 1887, hired Alvah C. Roebuck to repair watches, and established a mail-order business for watches and jewelry. Bertha was born May 12, 1887. Bertha began life the same year that Sears and Roebuck began business.

John, who became a talented musician told how he and “Bert”, as he called her were running through the woods one day. She was ahead, naturally – being much older– but as she ran ahead of John, she pushed aside a limb and let it swing back into his face.

His eyes were badly bruised, so they went back to the house where the parents, not knowing anything else to do, put John into a room, pulled shades and left him to heal in the dark. Someone gave him a fiddle to help pass the time. John, with a God given instinct actually became very good playing it. He learned songs by heart and played by ear. But when he was finally healed well enough to be removed from the darkened room it was discovered the fiddle was completely out of tune. Someone tuned it and John had to learn the songs all over again. But it was the beginning of a great love affair, John and music. As he grew older there was hardly an instrument he could not play. And, it also could be said that if he did not have an instrument to play, he certainly could make one.

Although the five acres, including the lake, were left to Bertha and John, Bertha eventually became the sole owner. John had borrowed from his sister on so many occasions that he finally just signed the property over to her. She allowed John and Esther to continue living there, at no charge for several years until Esther and the boys finally moved to Nashville in the early forties. There were times when the groceries Bertha, brought on weekends was the only thing Esther and the boys, had to eat.

They especially enjoyed the cookies that Auntie and Uncle Russell brought from a bakery on eighteenth avenue; less than a block from the little house where she lost her son about fifteen years earlier. The cookies were priced lower because they were broken or too ill shaped for the Bakery’s regular sale. But do you think three little country boys objected?

We have already pointed out, and will more times in our story, how important that house was and the many roles it played in the lives of many in the Setters family.

We have already pointed out, and will more times in our story, how important that house was and the many roles it played in the lives of many in the Setters family.

The numbers are attached to the house but in this picture of Bertha and Raymond standing on the front steps, seem to be sitting on Bertha’s head, much like a Halo.

The earlier pictures of 1116 Buchanan were taken by an old box camera probably sometime in the twenties. Although not identified, but her image is indicated by the small white star, the woman on the bench and standing by the swing set is probably Carrie Setters, Bertha and John’s mother. There would not be any other elderly lady at that house at that time. Carrie was born in 1870 and died in 1930, year before her husband, James, Bertha’s father and Bertha’s nephew Jim’s namesake.

1116 Buchannan Nashville, Tennessee

1116 Buchannan Nashville, Tennessee

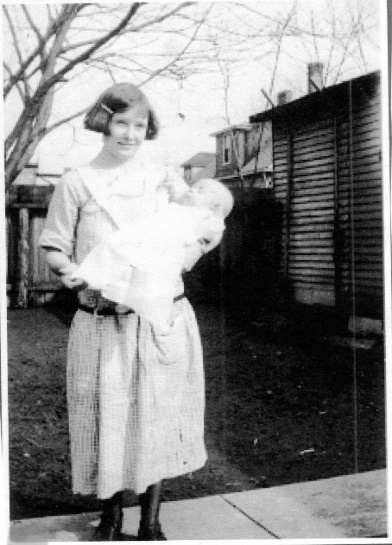

The reasons all of our older pictures were in black and white and appear to be posed is, that’s the way it was done back then. And the camera and film industry only doing black and white. Esther Setters stands proudly in the back yard of, you guessed it, 1116 Buchannan, holding what is believed to be the first black and white picture taken of John Raymond Setters, her second son, born in October of 1924.

That back yard was the setting for who knows how many box camera snapping’s in the years that Bertha lived there. Part of that back yard, behind and to the right of Esther, also served as a chicken pen in the late thirties.

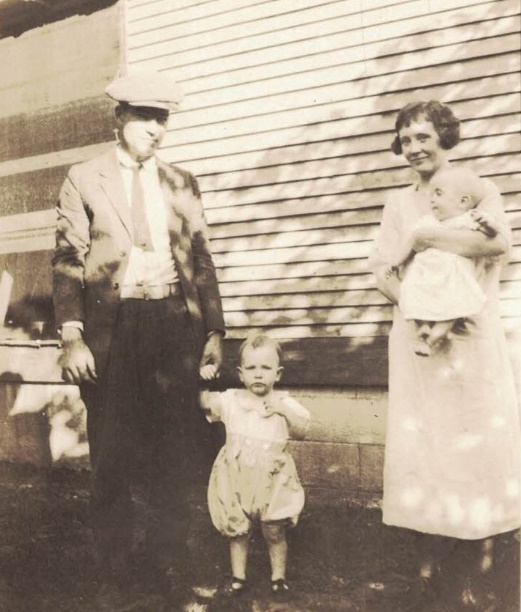

The adult couple standing by one of the tame mulberry trees in the back yard is of course, Esther and John.

Esther and baby Raymond

Esther and John

This young family, also standing in the backyard at 1116 Buchannan, is John, holding Harold’s hand and Esther with little Raymond in her arms. This was taken around Christmas in 1924.

If you have any doubts about the identification of Esther, just look at her hairdo

That backyard was also the place these boys and their little brother Jim, would use as a playground during family visits. As far as is known, it was never used for afternoon gatherings and casual chair sitting. For many years there were the chickens, in the large pen, and Bertha had a habit of keeping a dog or two.

The corner is vacant now. Nothing there but memories and a vacant lot bordered by various kinds of business.

Raymond’s wife Vickey does not warmly remember Bertha, or “Auntie” as the three nephews referred to her. She wrote for this story the following experience with Bertha.

“I have some not too pleasant memories of Auntie myself. I just overlooked them.

I needed $200 years ago and got up the nerve to ask her for it until payday.

She said ‘Why, of course, Vickey. I’ll be glad to.’ So, I told her I would come out from Brentwood on my lunch hour, and we would go to the bank as she suggested. When I got there, she was on the porch with one of her men boarders, in her old dirty green winter dress that she wore summer and winter (Raymond finally caught it off her and threw it away). I asked if she were ready to go and she said ‘Well Vickey, I just don’t have the money.’ So, I tucked tail and went back to work and somehow survived what I needed it for. That was a Friday.

On Saturday she called me to come over that someone had gotten into her Bank-account and took all her money (which she had told me she didn’t have). I looked at her bank statement and told her I would call on Monday. I found out the reason — she had transferred the money to a savings account but still had plenty in her checking account.”

Bertha, as many of us do, had drifted into a state of mind, in her seventies, in which she failed to appreciate what others were going through. Also, like so many of us, as we get older, lacked the understanding that she could participate in the lives of other of life’s travelers in a more positive way.

In short, she had eased into a state of being a grouchy, selfish old lady. She had shown compassion in her earlier years for her brother, John, John’s family, but somehow this had dissipated as she had grown older. And now she was applying her selfishness to Vickey who had added happiness to one of Bertha’s nephews.

This young lady, Vickey Ponter, had luckily landed into the lap of the Setters family. Bertha, who had lost a son years ago, and who had struggled through four marriages, recently buried a brother, and about twenty years earlier, a father, mother, grandfather and struggled through years of fighting the glass ceiling in the insurance industry, should have known better. But the scars of life covered over any human affection for this young lady standing in front of her. Bertha was unaware that this pretty wife of her brother’s namesake could have easily slipped through the fingers of fate and become part of someone else’s family.

Vickey had said farewell to her three brothers in World War II. She and her mother and father had seen these sons and brothers come home very changed people. Vickey’s father knew that his one daughter needed to leave the country of northern Alabama and become an adult that all indications were beginning to show she could be. So, this immigrant father sold some of his precious property to get the money to finance his daughter’s future. And this is the young lady that Bertha selfishly and deliberately refused a small loan. One more thing. Her father and the statue of liberty were both born/created in 1886; both of them with parts made in Europe, then brought by ship to the United States.

Vickey had said farewell to her three brothers in World War II. She and her mother and father had seen these sons and brothers come home very changed people. Vickey’s father knew that his one daughter needed to leave the country of northern Alabama and become an adult that all indications were beginning to show she could be. So, this immigrant father sold some of his precious property to get the money to finance his daughter’s future. And this is the young lady that Bertha selfishly and deliberately refused a small loan. One more thing. Her father and the statue of liberty were both born/created in 1886; both of them with parts made in Europe, then brought by ship to the United States.

In addition, Mr. Ponter returned to the forest to make more barrel staves to pave the way for his daughter’s future.

In addition, Mr. Ponter returned to the forest to make more barrel staves to pave the way for his daughter’s future.

Oh no, He didn’t sell the old homeplace, where Vickey was born and raised, it was some additional acreage he had acquired through the years of working in the forests.

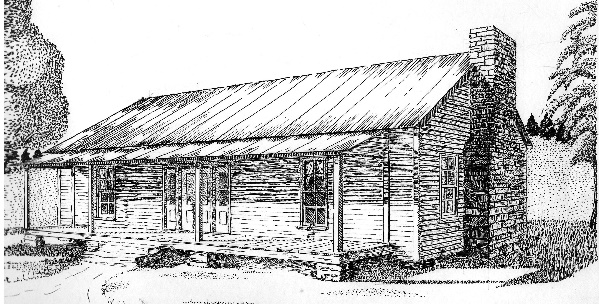

This pencil drawing of Vickey’s early home in Alabama was done by Jim and Vickey’s very talented friend and Jim’s former Howard High School friend, Raymond Proctor.

Proctor was a very talented artist and was the envy of Jim’s drafting class at Howard High School in Nashville.

The author of Ladies of Setters Lake, has named Proctor’s Mother as one of the Ladies. You will read why he did.

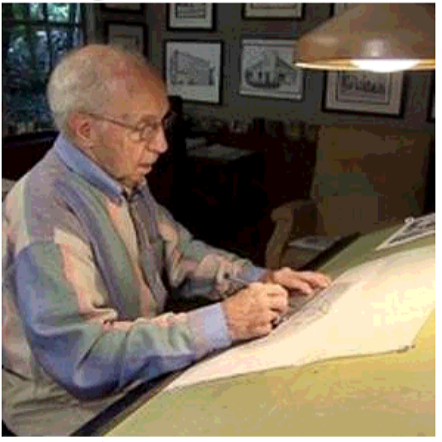

. Raymond Proctor in his home studio in Joelton, Tennessee

While Raymond was earning medals in the United States Navy during World War II, things were continuing at the lake on Little Marrowbone. By now the property was overgrown, the little house all but unlivable, and the lake? Well, time and circumstances have their ways. And the lake was, by now, just a dent in the earth. But for Raymond, it was his home, where he started and like many of us, and particularly those whose young lives were so harshly interrupted, a way to put things back together. In the assembling of events and lives of the many participants of our story it sometimes is difficult to find exactly where some of these incidents are to be placed. You were warned from the start that people and places would appear, fade and sometimes reappear as years unfolded.

So, let’s delve a little into what was and had been going on in Raymond’s life. He and Vickey had lived for a while in Memphis. It was there their son came into their lives. It was in Memphis where they strengthened their marriage and it was there, they became parents of their first and only child, a baby boy they named John Emanuel. John after  his own dad and grandfather and Emanuel after Vickey’s father.

his own dad and grandfather and Emanuel after Vickey’s father.

The plaque you see with Raymond’s picture hold the medals and ribbons that he earned while serving in the Navy during World War II. Most of his time was spent serving on invasion crafts as a machinist, although that involved more during combat than just keeping the engines running. He had to shoot back at the enemy. Raymond is proud of his work in underwater demolition; getting rid of enemy structures installed to keep the landing craft from the beaches.

His demeanor was to always be courteous, but he could also be quite mischievous.

We all know that war, as has been pointed out in our story, has a way of changing things. Sometimes for the better, but often the changes that occur are superficial and at best, temporary. But World War Two, that lasted less than four years for the United States, altered our culture dramatically and permanently. The Lake was not sparred. The change was obvious by what was not done rather than what was done.

The trees along the edge grew bigger, the fresh clear water from the creek did not enter. What was once a source of fun and entertainment became a sunken area of muck, moss and mud. The only creatures that now enjoyed the place were snakes and bugs.

Raymond did not have anything to approach Bertha with but his desire to live again on his old home place. In 1974 Jim approached her with six thousand dollars cash and she sold it to him. Was he the first to offer her money for the by now unattractive five acres? Was she wanting to keep the place in the family? We’ll never know.

Bertha did not have the kindest demeanor as an adult, at least as far as some members of the family were concerned. The boys never gave it a thought, but all of the adults surely knew that Bertha never really got over that fateful July day in 1919. Was she attempting to transfer a motherly love to the little boys, her nephews? Was one of them, two or all three a replacement for her departed son? Did she envy her little brother?

She often bought her nephews clothes; shoes and many times took one home to stay all night. There was good eating but there was also a little bit of tension. When Auntie came out on Sunday afternoon, there was always delightful food, cookies and things the boys seldom had at home. There was just not enough money. She allowed her husband, Russell Dickerson, at the time, to slip a “plug” of sweet tobacco to Raymond, even though both were aware that his mother was firmly against his chewing.

One day in the late nineteen-seventies Bertha was visiting Jim and Dana in their new home beside the newly redeveloped lake. Keep in mind that she was born in 1887. During their casual conversation, she remarked that her brother had married a woman from Kansas.

Nephew Jim was shocked to say the least. It was the first time anyone close to him, and especially a member of the family, suddenly just blurted out such a surprising and obvious dementia phrase. Of course, her brother, Jim’s father, had married a woman, Jim’s mother, from Kansas. Everyone knew that. Suddenly and without warning, Bertha became a stranger.

The memories of those years of being with that woman from Kansas the mother of Bertha’s nephews, including the one sitting right there with her, were all gone. She didn’t even know who Jim was. It was the beginning of the end of a woman who had been in charge of her life, all of her life.

In the opening of this story the author alluded to the fact that most of us wait till it is too late to gather information from their ancestors about their ancestors. Had Jim already begun this process, which he had not (in fact at the age of fifty such a thing was furthermost from his mind) it was already too late. Bertha was no longer a viable source. No matter, Jim would not pursue the subject in another thirty-five years anyway. And Bertha would not be present to fill in the blanks. And they would be legion.

Bertha had held an executive type of position with the insurance company in Nashville as executive as a woman could be in those times when the glass ceiling hovering closely over the business world kept women in their place. In her neighborhood in North Nashville her home was where people went for help in their income tax returns, or to have a document notarized. They knew that a knock on her front door brought needed solutions. It was done discreetly and with little fanfare. They paid a very small fee.

As is often mentioned, her home at 1116 Buchanan was an oasis for the family of her little brother. She would be the anchor in the sometimes, turbulent waters of life this country family would oftentimes confront. The demeanor she often projected has caused some, even some members of her Little Marrowbone relatives, to find fault in how she treated others. But there was food on their table when there would be none, shoes on little feet, where magazine pages covered the holes in the soles, they knew she would be there.

Perhaps she did those things because her brother failed to be the provider as he should have. Or, as some suspected, it gave her occasions to be in charge.

Bertha’s house on Buchanan, now long gone; it was demolished and became simply a vacant lot in 2016, was one of many from the beginning of Buchanan Street at third avenue north to where the city limits ended at eighteenth avenue. Why was it named Buchanan? Some say it was a tribute to President James Buchanan.

Described by some as being gay, Buchanan was the last president to serve before the civil war. Abraham Lincoln won the election over Buchanan and as he sat in a carriage beside James Buchanan, the outgoing president (Buchanan) reportedly said to him, (Lincoln)”If you are as happy entering the presidency as I am leaving it, then you are a very happy man. “In his book The Nashville I Knew; Jack Norman points out the naming of several streets in Nashville for the nation’s presidents. Buchanan seems to fall into that category. That’s a shame; there were Buchanan’s who played important roles in the early days of Nashville that would best be noted. According to Wikipedia, Nashville was named after Revolutionary War General Francis Nash in 1784, and it would appear that Buchanan Avenue or Street was named for Fort Buchanan that was under attack by as many as Indians.

The Nashville Historical Newsletter wrote about another Buchanan who would have been better qualified for the tribute:

Perhaps the wisest decision John Buchanan ever made was to marry Sarah “Sally” Ridley (1773-1831). Sally was one of the first white females born in what would eventually become the state of Tennessee. Along with her father, Revolutionary War veteran Captain George Ridley, she arrived in the Cumberland settlements about 1790. Her family established Ridley’s Station in the area of today’s

Nolensville Road and Glenrose Avenue. Sally, a large woman with a large personality, was destined to become a legend in much of the eastern half of the United States.

Throughout the Battle of Buchanan’s Station, Sally, nine months pregnant with the couple’s first child, was the heroic voice of victory. She encouraged the riflemen at every turn, molded bullets when the supply ran low (reportedly by melting her dinnerware), blocked another woman in the station from surrendering herself and her children to almost certain death, and helped fool the Indians by a “showing of hats.” Sally’s uncommon spunk was extolled by biographer Elizabeth Ellet in her 1856 volume, The Women of the American Revolution, which referred to her as “the greatest heroine of the West.” Periodicals from as far away as Boston immortalized Sarah, some fancifully, and she was listed in at least two national encyclopedias of biography (Appleton’s and Herringshaw’s).

John and Sarah Buchanan had thirteen children: George, Alexander, Elizabeth, Samuel, William, Jane T., James B., Moses R., Sarah V., Charles B., Richard G., Henry R., and Nancy M. The Buchanan children and grandchildren intermarried with members of other settlements around Buchanan’s Station, their families becoming important not only to Davidson County history but also to that of neighboring Rutherford and Williamson counties. Eventually the Buchanan descendants spread to all parts of the United States, and accounts of their accomplishments and contributions to the nation could fill volumes.

Buchanan’s Station also has significant associations with local Native American history. It was a confederacy of Creeks, Cherokees, and Shawnees that attacked the Station in 1792. During the battle, Chiachattalla (also known as Kiachatalee, Tsiagatali, Kittegiska, and Tom Tunbridge’s son), an especially dauntless warrior, was shot near the fort. As he lay dying, he reportedly continued his efforts to set the structure ablaze by fanning the flames with his last breaths. Also killed in the battle were “the Shawnee Warrior” (Cheeseekau, a brother of the great Tecumseh) and White Owl’s Son, brother of Dragging Canoe. The great Chickamauga chief John Watts was shot through both thighs but was removed from the battleground in a litter and later recovered. For a partial list of Indian casualties at the Battle of Buchanan’s Station see American State Papers: Indian Affairs 4-331.

Today John and Sarah Buchanan are almost forgotten. Very few citizens know that their graves, with the original headstones, survive in Buchanan’s Station Cemetery, the last vestige of the pioneer settlement.

The educational and inspirational lessons of their lives have been largely squandered, and the story of the Battle of Buchanan’s Station has been all but lost. Believing that the Buchanans are an integral part of early Nashville history – see the first chapter in Harriette Simpson Arnow’s Flowering of the Cumberland – a number of concerned Nashville-area citizens have formed the Friends of the Buchanan’s Station Cemetery, with the goals of remedying years of neglect of this historic site and of restoring one of Nashville’s founding families to its proper place in our historical consciousness. (2011)

If the descendants and family members of Sally Buchanan, don’t mind, I will digress somewhat in our story and use some of my more modern elements of life and rely on whatever bit of humor that might possibly be squeezed out of this story about Sally Buchanan. No doubt at all about Sally being an important part of Nashville’s history, and I (the author) would certainly approve of her having not just a tourist sign praising her, but a more than full size statue at the State Capital building to replace some of those Confederate monuments being done away with.

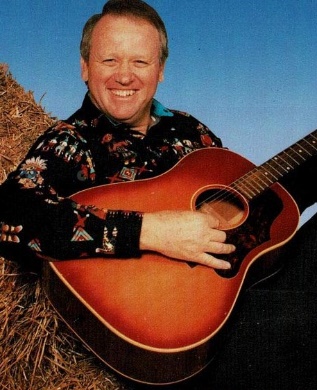

During my nearly a quarter of a century living in Wichita, Kansas and more specifically when I was an employee of KFDI radio, we did what we called remote broadcasts. This meant we did a live broadcast from a sponsor’s place of business and if the sponsor paid for it, a live band (usually the Wichita Linemen) and an appearance of Ole Mike Outman, Part owner, of the Great Empire Broadcasting Inc.

One of Oatman’s songs was entitled “SALLY WAS A GOOD OLE GIRL”. He would sing it at every remote, and the audience loved it. The lyrics included these words:

“Whatever the REE quest, she gave it her best, Sally was a good ole girl”. No disrespect is intended, but I couldn’t help thinking about Oatman’s singing, that, live and wondering, if he had ever read about Sally Buchanan’s role in Nashville’s (the mecca of country music) history. The thought never entered my mind, especially as I listened to Mike sing live, until I did my research while writing, THE LADIES OF THE LAKE. And, I doubt, into Oatman’s. And I am a Nashville Howard High School Graduate. Mike sure wouldn’t know, he is a Marfa, Texas native.

“Whatever the REE quest, she gave it her best, Sally was a good ole girl”. No disrespect is intended, but I couldn’t help thinking about Oatman’s singing, that, live and wondering, if he had ever read about Sally Buchanan’s role in Nashville’s (the mecca of country music) history. The thought never entered my mind, especially as I listened to Mike sing live, until I did my research while writing, THE LADIES OF THE LAKE. And, I doubt, into Oatman’s. And I am a Nashville Howard High School Graduate. Mike sure wouldn’t know, he is a Marfa, Texas native.

Sally was only eighteen years old, stood over six feet tall and weighed 250 pounds, remember, and was nine months pregnant. So, she would have no trouble at all in defending her honor. Sally, in person, also was not one of the features of our remote broadcasts, far from it. Other than her physical dimensions we have no earthly idea what Sally Buchanan looked like. I don’t. Is that discrimination or what? So, get on the bandwagon Ladies. Buchanan is no longer one of Nashville’s notable streets, so we are a bit late in giving Sally her dues. Both, Sally and Ole Mike Oatman are dead now. Him at age 63, and her at a younger 57.

Her in 1831, and Ole Mike in 2003.

Bertha had married four men. All died before she did. The last, a drunken bum who had taken advantage of her fading mental ability, shot himself in the head with a shotgun, at 1116 Buchanan. Bertha heard the shot and was the first to see the bloody mess in the bed. Gradually her health deteriorated, and she was placed in a hospital. Jim, Dana, Vickey and Raymond were visiting her one day and Bertha was reluctant about drinking water. She had indicated to Vickey earlier that she was afraid of choking. She lay there for several more days. Death finally came November 26, 1976. It came six months and seventeen days shy of ninety years of living, longer than her mother, father, brother, son, or any of her four husbands. But two years shy of Leander’s ninety-two.

Her survivors and friends gathered at the Woodlawn Memorial cemetery at ten A.M. Monday morning November 29th. It was miserably cold and windy resulting in none of them accompanying the burial crew to the grave site. True to her living character, Bertha made the trip alone.

She had lived an interesting life that had lasted eighty-nine years, three months and one day. She was named Bertha. Some called her Bert. Those not part of the family knew her as Miss Bertha, Mrs. Rice, Mrs. Forte, Mrs. Dickerson, Mrs. Tidwell; but to her nephews, she was always Auntie. Even the two who had lived. nearly a century and of course the one who flew those missions in three wars to make sure she would always have her beloved Coca-Cola.

Bertha, swimming in the lake before it became her lake, (She is the lady on your right) when it belonged to her grandfather, Leander Setters. When her grandfather, Leander Setters died, in 1932.

Bertha, swimming in the lake before it became her lake, (She is the lady on your right) when it belonged to her grandfather, Leander Setters. When her grandfather, Leander Setters died, in 1932.

Twenty-four years had gone by since Leander and his men scooped out what was remaining of the pond that the previous owner, a Mr. Winters left of what had begun as an ice pond.

The dance hall, which was responsible for the notoriety of the lake is in the background with the people standing lakeside. Bertha’s uncle Bill wrote Leander’s will, at his choosing, which gave the lake and its five acres to Bertha and John’s father, James Madison Setters, and his brother Bill Setters, and so, ultimately to John and Bertha. You should have already read about that so we will let it rest.

Forty-two years later, James’ grandson, (Jim the author) had to pay Bertha, James’ daughter, and Jim’s Aunt $6,000.00 for five acres. But by then, it was a quagmire, nothing, but a swamp. Jim the author was like his brother John Raymond and wanted so badly to return to their old homeplace. The $6,000.00 was ten times what his grandfather, James, had to pay HIS father thirty years earlier, in 1930.

And poor Dana, when she first learned about the prospect of building a lake

only had to listen to the crickets and treefrogs, that just go “Beep”.

The Swamp

The Swamp

.

While it was Bertha’s Lake until 1974 when she sold it to Jim and Dana for $6,000, the lake had depreciated to this.

From 1974 until Jim and Dana sold the lake in 1989 it looked like this.

From 1974 until Jim and Dana sold the lake in 1989 it looked like this.

The same camera angle as the picture earlier of the swamp.